Stef is a freelance director who has been the Artistic Director of nabokov and the Associate Director at Paines Plough and the Lyric Hammersmith.

At the time of this interview she had been directing A History of Water in the Middle East by Sabrina Mahfouz. She had also recently directed Lit by Sophie Ellerby and Paines Plough’s Roundabout season 2019 – Daughterhood by Charley Miles, On The Other Hand, We’re Happy by Daf James and Dexter and Winter’s Detective Agency by Nathan Bryon.

For Paines Plough: With a Little Bit of Luck by Sabrina Mahfouz, Island Town by Simon Longman, Sticks and Stones by Vinay Patel, How to Spot an Alien by Georgia Christou, Hopelessly Devoted by Kate Tempest, Blister by Laura Lomas, and as Assistant Director: Wasted by Kate Tempest.

For nabokov: Last Night by Benin City (Roundhouse/Latitude) Box Clever by Monsay Whitney (Marlowe Theatre/Roundabout), Storytelling Army (Brighton Festival) and Slug by Sabrina Mahfouz (Latitude).

For the Lyric, as Co Director: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as Associate Director: Mogadishu (Manchester Royal Exchange), as Assistant Director: Blasted – winner Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre 2011.

Other Director credits: Yard Gal by Rebecca Prichard – winner Fringe Report Awards for Best Fringe Production 2009 (Oval House) A Tale from the Bedsit by Paul Cree (Roundhouse/Bestival), Finding Home by Cecilia Knapp (Roundhouse), A Guide to Second Date Sex and When Women Wee by Rachel Hirons (Underbelly/Soho) and as Assistant Director: Henry IV by William Shakespeare (Donmar/St Anne’s Warehouse)

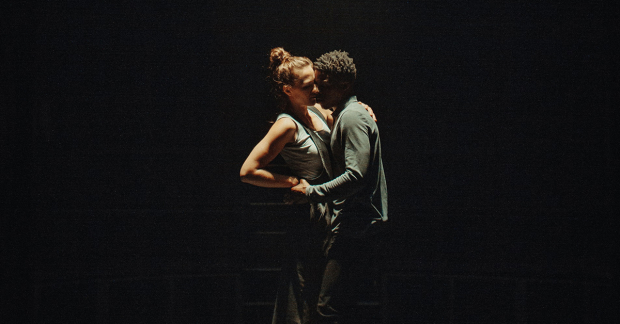

Photo by Rebecca Need-Menear

A rhythm that’s within me

Phil: What is theatre?

Stef: It is live storytelling in a shared space, for me.

Phil: What music are you into?

Stef: Drum ‘n’ bass drives me. I’m either making theatre or I’m in a drum ‘n’ bass rave. Music has always been a massive part of my upbringing. I was always surrounded by it; my dad used to run raves and have his own parties. Then, during that time when I was in my teens, it was a community and a space that I really needed. I really needed to feel like I was a part of something and to belong. Since then I’ve experienced every emotion on the drum ‘n’ bass dance floor: loss, grief, love, pain, joy, like everything. It feels like it’s a rhythm that’s within me. I don’t know, I can communicate in it, in a weird way, it just feels like that’s my tempo.

Phil: What characteristics of drum ‘n’ bass inform your theatre work?

Stef: I don’t know if I’ve ever really thought about how it directly impacts it, but I suppose it’s the energy of it. A lot of my work is quite bold or quite vibrant and quite energised, so it’s informed by that rhythm and energy, but it can also be melodic and beautiful. There’s so much drum ‘n’ bass that I listen to that’s all about pain and blues and love and loss. I feel in drum ‘n’ bass to be honest. When I think of a story or an emotion that I might want to support or portray, or an energy, I think in drum ‘n’ bass. For example, I did a show recently with the sound designer Dom Kennedy called On the Other Hand, We’re Happy. It’s a love story and there’s this one track that I kept hearing and feeling called Her Waves by Halogenix. I sent that to Dom and told him that when I think of love in this play, this is the track. Then he takes it from there and works his magic with that energy or that vibe that I’m trying to create. So, I think it directly affects my work because I go for that first, to show how I feel or how I think something should feel and then that directly impacts a mood or an energy or an atmosphere in the work.

Phil: How does the community around drum ‘n’ bass inform your theatre work?

Stef: I think it has directly influenced the type of work that I make and continue to make. My raver friends never thought theatre could be a place for them, they’d never really gone. So, when me and Sabrina [Mahfouz] first worked together on With a Little Bit of Luck, a UK Garage gig theatre production, we really wanted to make work directly for our raver friends. It was important that we provided an experience where they felt like they could relate to the characters and the stories. We wanted to break down those barriers that theatre still, unfortunately, has for a lot of people. Since then I’ve continued to experiment with that form of storytelling in a gig atmosphere.

Phil: Why is it important to you that they go to the theatre rather than going to a rave?

Stef: I’m not trying to stop people from raving at all! So, everyone, continue to rave! But I think everyone should have the opportunity to experience theatre and storytelling. Then people can make an informed decision about whether it’s for them or not. It’s important because there is something really powerful about being able to relate to versions of yourself, whether it helps us understand our lives or make a change. I remember my good friend, Deefa MC, coming to see With a Little Bit of Luck, and there’s a character called Tee who scribbles his bars while he’s at raves on the backs of receipts, and he was like, “Oh my god, that’s me!” There was a magic that happened in that moment when he could see himself on stage. Theatre is also a place where you realise that you’re not alone. I actually think there’s a healing thing that happens when you experience that.

Phil: Is there something in the bodily experience of raving that informs how you work with actors’ bodies or spectators’ bodies?

Stef: Raving allows me to access a certain energy that I can’t just walk around with every day. I have two types of rave energy: one which can be more aggressive and there’s certain types of drum ‘n’ bass that allows me to have that energy on a dance floor and it’s a safe space for that to come out in. The other type of energy feels quite floaty and spiritual. I find it fascinating how music and movement responds to space. If you’re outside, dancing to more old school music, you’re raving up and you’re very open, because you’re raving to the sky, to the clouds. But then if you’re in a dark night club with low ceilings, dancing to jungle music, your whole body becomes more inward. Now that I’m saying this, I’m seeing how I could relate it to using Laban technique in the rehearsal room.

I’ve done some work with Paines Plough in the Roundabout recently and, because there are no props or set and you’re three hundred and sixty degrees in the round, it meant that we did a lot of work with movement directors about the physical toolkit. I’ve also been working with Laban qualities in rehearsal rooms, whether you’re floating or flicking or punching, Maria [Koripas] definitely used them in A History of Water in the Middle East. Those qualities help us understand how we are delivering the lines with voice and movement and how that might change the impacts they have on an audience.

A mixture of different energies and tones and rhythms

Phil: How do the ideas of musical structure inform your construction of a piece of theatre?

Stef: There are certain structures to music and tracks that I think really help me when constructing and composing a piece of theatre. For example, you have different dynamic changes within tracks, you have an intro and build, then you have the drop and then you have a break down again. So, in theatre asking questions like: what are we building towards? Is this the climax? Is this the drop? Is this the break down moment? Is this the intro? What do we need to get across in our intro?

I’ve spent quite a lot of time in raves and a DJ might occasionally go in with some harder drum ‘n’ bass and then half-way thorough their set they go half time and then go back to heavy drum ‘n’ bass at the end, but that can sometimes feel a bit disjointed. There’s a reason why the DJ has decided to do that, but if I’m getting into a zone and then you completely change the rhythm, that can sometimes not go down well.

It was really hard to get a sense of what the rhythm of A History of Water in the Middle East was until we were in previews because things were always shifting and changing. Sabrina is an artist of absolute integrity and will constantly interrogate her work and say, “No, that scenes not working, here’s another scene.” That felt a little unsettling as I couldn’t quite get the sense of the rhythm and the arc of everything until previews.

But then it was really fascinating that what we created is something I haven’t really created before. It was a mixture of different energies and tones and rhythms. It didn’t follow any pattern or structure that I’ve ever worked on before. It defied any arc that I would normally try to put in. There were so many climactic moments, which is amazing actually and really formally exciting. There still was the thread of the spy narrative within it but actually tonally because of form and the rhythm of the music, it peaked at loads of different times, which is new for me.

We talked about story structure a lot in the rehearsal room. I’ve been reading lots of books about it and there was one written by a guy called John Yorke and I was like, “Ah, this is the innate story structure!” But Charlie Josephine, an incredible playwright, started to talk to me about it, and they said, “Yeah, but all of those books have been written by men and actually follow the male orgasm. What happens if you create a structure of a play that follows a female orgasm?” I feel like Sabrina’s play represents that more than the normal story arc in terms of the rhythm of things.

Phil: How has the work you’ve made responded to the space it’s in?

Stef: For With a Little Bit of Luck at the Roundhouse we were way less in control of navigating people’s experiences in the main space at the Roundhouse. It was a lot easier for people to stay with the story in the small studio space than it was in the big space. The big space opened up more of a sense of freedom: if you really wanted to stay with the story, you’d be up front, whilst people in the middle were only dancing, not really listening and people at the back were at the bar having a good chat and occasionally being like, “Oh my god, that’s a sick garage tune.” It’s right that we hand that control over. I’m creating work that allows people to be in that space how they choose to be and to not be attached the outcome. One of big aims for that show was to create a piece of work that my raver friends would feel comfortable in. If that means they feel comfortable in that space, they get a bit of the story, but they spend most of the time talking about when they were raving at the bar, that’s still a win for me. It’s also a win that there was someone right at the front who got every bit: the story and the music.

I think we create something, we create stories and, as long as I’m making it with the best of intentions, and what I mean by that is creating it with absolute love and kindness, the impact that it has on the rest of the world or each individual is none of my business. I have to have faith that it’s doing what it needs to do.

Phil: How does your approach change when you work in non-traditional spaces?

Stef: Even if you’re in a non-traditional space, you’re still trying to tell a story, so I think it’s really important that you steer an audience and give them a toolkit of how to engage in the space. In With a Little Bit of Luck, Nadia, played by Seroca Davis, tells the audience they can dance along. Sabrina, in her writing, gives you a framework in the first five minutes of how you can use that space: this is what’s going to happen, this is who’s who, there’s going to be some music playing and you can dance along if you want to. Some people need to know the framework, especially in non-theatre spaces, so that they stay with you and go on the journey with you.

Phil: How do you specifically signal moments that demand focus in non-traditional spaces?

Stef: It’s tricks. Again, it leads me back to music and using music structure to help. For example, if you’ve just had something that is constantly scored by music in a gig theatre environment, a way to get people’s attention when they really need to focus is absolute silence. Clear dynamic shifts, so the energy and everything changes. In With a Little Bit of Luck we’d have these bursts raving to garage music and then there’s a dynamic shift and we’d bring the music down underneath a piece of text. Then people know that it’s no longer the space for them to dance in anymore because someone is about to talk. Lighting can help, but especially in gig theatre, it’s playing around with the different dynamic shifts in music.

Photo by Craig Sugden

Being seen and being heard

Phil: I know your time at Ovalhouse was particularly formative, how did your mentor Nicholai LaBarrie ignite your passion for theatre?

Stef: Nicholai LaBarrie is a very special human. I suppose as a young human, it was a really difficult time for me actually. Having Ovalhouse as a place to go to as a way to express something and to play other characters so I didn’t have to be me for a couple of hours. Nicholai was able to allow each young human to develop and organically grow and be ourselves. He didn’t try to make us be anything other than what we were. He saw us, he heard us, in a really organic way, so we didn’t have to be anyone else other than ourselves. He fully accepted who we were for all of our flaws. My brain was always overactive and if it wasn’t used, I’d cause trouble. He was very good at just going, “Well, here’s more to do. You’re going act in this play, but you’re going to stage manage it as well.” He is amazing at understanding what a young human needs to be able to be the best version of themselves. He gave us love and nurture and provided opportunities that we could excel in or achieve something in. He created a supportive environment and he’d be one of the first people that I’d go to and say, “This is what’s going on, I don’t know what to do.” He provided that support at a time when I think it could’ve gone either way for a lot of us. If I didn’t have that place to go to and something that I cared about, I’m not too sure what path I would’ve gone down. He ignited a passion and gave me a sense of achievement in a really nurturing way that allowed me to be me.

Phil: I know you’re still cultivating your ideas around democracy and non-hierarchical rehearsal rooms but how do you begin to marry those with the realities of being a director?

Stef: ‘Still cultivating’ is a very good way of putting it. I haven’t really had the time to process things after A History of Water in the Middle East. I just think that there is an innate thing in all of us as human beings that we want to be seen and heard. Unfortunately, I’ve noticed that a lot of people’s experiences of making theatre are that they haven’t been seen and they haven’t been heard. Being ignored like that takes a long time to heal. So, number one, it’s really important to see and to hear everyone in the rehearsal room. I don’t have all the answers and I’d be lying if I said that I did. I definitely might have a clear understanding of the direction I want to move something in, but I think it’s really important that it’s a collaboration and you’re not going, “This is solely what it is.” There’s a reason why you have a lighting designer and a set designer and actors, it doesn’t all have to come from me. Everyone’s there for a reason and they have certain skill set. So, how do you nurture and nourish and get the best out of people for them to really step into their skill and share it? I think that’s to see and to hear people. I think it’s to empower people. If you can support people to share their skill set, then ultimately, it’s my job to steer what they’ve put into the room. That’s a far more enjoyable way of working. I also think that you get an investment from your team if everyone feels like they’ve been seen and heard. If they’re putting stuff into the rehearsal process, then they’re completely owning the characters that they’re playing, they’re completely owning the music that they’re contributing. Then, ultimately, we have a shared investment and a shared goal. As a director, you might have a vision but if you’re truly working in a collaborative space, sometimes the outcome will be different. A History of Water in the Middle East is not 100% my vision, and I don’t think that it ever could’ve been, but that’s what I find really exciting about the show that we made. It feels like an absolute expression of every single human-being in that room. It’s uniquely filled with all our energy and expressions. It’s a bit of everyone in there and that’s why it’s so formally exciting