Rachael Walton is co-founder and co-artistic director of Third Angel, a theatre company making entertaining and original contemporary performance that speaks directly, honestly and engagingly to its audience. Walton established Third Angel with Alexander Kelly in Sheffield in 1995. The company makes work that encompasses performance, theatre, live art, installation, film, video art, documentary, photography and design. They use styles, techniques and interests discovered in more experimental work to create new theatre that plays with conventional forms while remaining accessible to a mainstream audience.

A massive melting pot

PC: What is theatre?

RW: Peggy Phelan talks about how the relationship between the performer (the person doing the performative act) and the audience (the recipient of that act) is like an exchange of letters. The performer offers something out and the audience member, within that moment, accepts it and their reaction is their letter back. So if I was really going to take it down to the fundamental: what is theatre? Then for me it’s that exchange.

PC: How is your theatre practice informed by visual art, live art and film?

RW: For the first eighteen years, to a certain extent we chose not to use the word ‘theatre’: our title was ‘Third Angel’ – we weren’t Third Angel Theatre Company. We didn’t want the work that we created to be limited to that notion of ‘theatre’ and at that point we were restricting theatre to where it happened – the building. But recently we’ve decided to reclaim the word for us and say that we make theatre, because actually what we want to do is broaden the notion of what that is. The way we think is that there’s our itch, there’s our scratch and there’s our piece of work. The itch and scratch hasn’t necessarily got a form associated to it. We explore them in terms of research, making ourselves informed about what we want to do and then we start to think about what that should look like. The form that work takes on is very much dependent on what’s suited to the particular idea.

We see theatre as a massive melting pot with lots of different options to take all the time. For example, Cape Wrath, which Alex now does in a minibus, started off with Alex wanting to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps and take the journey that his grandfather went on. This journey was a myth within his family and he wanted to relive it but at that point we didn’t know what form it would take. Lots of our projects take on multiple ways of expressing themselves. The first version of Cape Wrath was photographic and it was on Twitter, then he started doing it as a performance lecture with slides and he did scratches at festivals. After that he brought it to me and said, “This is what I’ve got, I’d like you to direct it.” That’s when it ended up in a minibus and as a consequence all of the images had to go because we didn’t have the space to project them. Once we brought it into the minibus and had just fourteen people there was a different set of rules. We had to think about how to engage with those people within that space. It couldn’t just be a performance lecture in a minibus so instead it became about the shared space. The minibus held a different expectation and we had to give the audience ways they could actually feel that they were a part of the performance – part of that was offering chocolate and offering maps to the audience.

Fiction and truth blend to make the reality

PC: How do you blur the lines between truth and fiction or memory and imagination?

RW: The way we deal with autobiography operates on a lot of different levels within our work. On a basic level there is the work where we say, “This is us, this is what we’ve done, this is our response to it.” Class of ’76, 600 people and Cape Wrath are very much like: “This is me as a person/performer, this is my story and I’m sharing it with you.” There’s no blurring of the lines there.

The blurring of the lines happens when we offer you autobiography within a context of a wider fiction. An example would be, one of our early shows, Saved, a one woman installation piece. I would walk backwards around a room for anything up to five hours, brushing away each footprint. It was a countdown, a narration, of the breakdown of a relationship: the tiny day to day erosion that happens so slowly that you don’t really realise that it’s happened. There’s a good portion of that show that’s completely true and based on my experience but there’s also a good portion of it that’s completely made up. The element of the autobiography makes the performed act (or the notion of lying if you want) much easier because it gives the falsehood an authenticity. I think it comes hand in glove with when you’re operating within persona rather than character because there is always an element of yourself that’s present in that persona. The mix of truth and fiction and performance means it becomes something else – a new truth. I’m really interested in that.

PC: How does the fiction and the truth sit in a triangle with reality in those performance moments: is reality different to truth?

RW: Yes I think it is. I think! The Department of Distractions deals with the nature of truth and reality and where differences lie. I think fiction and truth blend to make the reality of that moment. The context of theatre means there’s an expectation from your audience that at some point they may have to suspend their disbelief. When you enter into that contract, what’s truth and what’s lies becomes blurred anyway.

We’re very explicit, with the work that is pure autobiography, that we’re telling the truth as far as we possibly can. Even with the more theatrical work, we’re not trying to lead our audience astray. I think it’s about using our own personal experience to create a richer theatrical language, and actually, autobiography is just a tool in our toolbox. By the time we do get it in front of the audience, the lines between what is true and what is not has blurred to create a new fiction for those people. In terms of our devising process I think there will always be an element of using ourselves, using our own experience, because we’re not investing in a Stanislavskian approach or a Brechtian approach. We use the notion that we are in the room – we are the right people at the right time to create this piece of work.

PC: Do you have an exercise in your process where you ask performers to use their autobiography and then blend it with fiction?

RW: One of our exercises is a bag exercise: we ask all the participants who are in the room to bring whatever bag they have with them and invite them to share the contents with the rest of the group. [There are rules that we always use with autobiographical work: share the stories that you want people to hear and share the stories that you would allow to be heard from someone else’s mouth. We make it clear that what you create and anything you share is within a safe space: none of those stories are used again.] So you choose to share from your bag what you want to share. We then ask them to choose one thing from the bag that’s going to be a true story (how they got it or what it means to them) and another item from the bag that is not true but on an equal level of complexity. We then go around the circle and we tell the first story, then we go around the circle again and we tell a second story, but it’s up to you which is the truth and which is the lie. You could also run that through as more of a performance – the autopsy of your bag, with the truth and the fiction alongside each other.

Dismantling the scaffolding

PC: How do objects and space drive your work?

RW: Both Alex and I work visually, that’s just the way our brains are wired. The visual really is as important to us as the text. I don’t think that either of us can ever settle until we know what the space is physically going to be. We work with a designer now, Bethany Wells, but for our first nineteen years, Al and I always did the design ourselves and that was quite important.

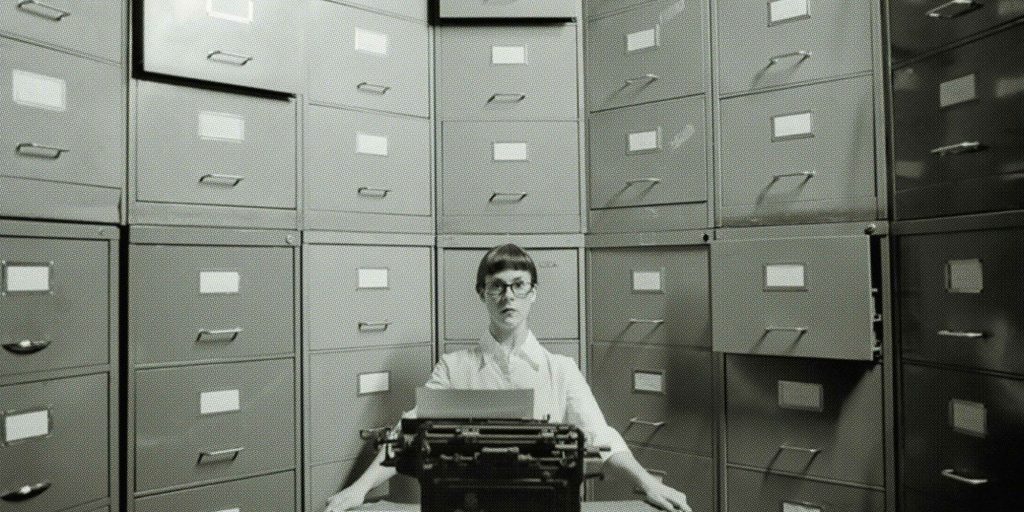

A lot of people use objects or costumes or something like that as starting points to improvise around, we don’t do that and we’ve never really done that. We may do that if we’re working with other people in a bigger group but for us it’s more about bringing something more conceptual: maybe a type of material, paper or liquid and then we can play with that. For Believe the Worst it was steel, we just knew it was going to be filing cabinets. So on the first day of rehearsal we had twenty-three filing cabinets and spent the next four weeks trying to work out what to do with them and what world there would be. Our more ‘live art’ work is often based on a stage image that we want to get to and the process is working out how we get there. For Shallow Water we started with the image of a huge bath with a girl sat on the edge and that evolved into it being about washing.

We tend to start working from a general theme, a general point of research and then we start to think: What is that world? How can we make that world? What can we bring into the room to make that happen? We may start working separately but even if we’re together we think sectionally and then find ways to link those sections together. We can’t make those links until we have a sense of the overall visual image and how the audience might be placed in relation to that image. We try different visual images and dismantle them, we may go away and come back and think, “That didn’t work – let’s start again.” We try and create exercises in response to the images – these are tightly structured, rule-based improvisations – we don’t spend hours doing free, spontaneous improvisations. Once we have a lot of these exercises, we try to connect them and then take the scaffolding down that’s around them, so the process of making it isn’t evident in the work that is shared.

Individuals that are there now

PC: Is there something in your toolbox that you return to in order to foreground the presence of an audience?

RW: The audience operates in the room as soon as we start making a piece of work – not as in actually being in the room – but there’s always that essence of who they are, where they are, what they’re doing – as much as as there is our who, what, where when and why. There’s always a discussion early on about what we want that relationship to be and how much we want the audience to be integrated in the piece of work.

An audience usually has particular expectations, there are unwritten rules around theatre performance today and those rules make people feel safe: you’re supposed to be quiet for instance and if there’s a seat, you’ll sit still and stay until you’ve finished. We consider the expectations our audience might come with and, if it fits the concept, we might play around with those rules. If you want to take one of those rules away you have a real responsibility and a duty of care to your audience about what’s going to happen to them after that. Once one of those rules has been taken away there is the thought that others, or all of them, might be taken away. That can be both positive and negative. You can make people feel uncomfortable if that’s necessary to the piece of work, but I think knowing why you’re going to make them uncomfortable is important. If you are going to use members of the audience within your performance then exploring what that means and accepting the consequences is important.

We look for different ways to explore that relationship with the audience – we don’t make ‘immersive theatre’ on the level that the term has become now but we’re always quite interested in how we can allow the audience to feel that they are part of the performance. We might get someone to play one of the characters, or get them to read cards, or ask them to give feedback, we might collect their story to use in the next performance, or allow them to change the space somehow. It’s about finding what’s appropriate, what would help the piece and what would help the audience’s experience. It’s getting performers to talk to people. When we’re working with people we say talk to the individual – an audience isn’t just this big thing that arrives – it’s two hundred individuals that are there now.