Tim Crouch is a playwright, actor and director. His work includes My Arm (Prix Italia 2004), An Oak Tree (Herald Angel 2005, OBIE 2007), ENGLAND – A Play for Galleries (Fringe First, Total Theatre Award, Herald Angel 2007), The Author (Total Theatre Award, John Whiting Award 2010), what happens to the hope at the end of the evening (with Andy Smith), Adler & Gibb and The Complete Deaths (with Spy Monkey). Tim has written a body of work for younger people including Kaspar The Wild, Shopping for Shoes (Brain Way Award 2007), the I, Shakespeare collection which includes I, Malvolio, and Beginners.

Tim also works regularly with two co-directors, Karl James and Andy Smith. Karl runs an organization called The Dialogue Project, based in London and Andy Smith is a theatre maker, writer and thinker. Read our interview with Andy Smith here.

A space to explore how as well as what

PC: What is theatre?

TC: It’s a place where we think together. It’s one of those quite rare places today where people can come together to engage in thinking that is not prescribed by an educational or religious doctrine or agenda. It’s a celebration of the human capacity to explore metaphor. It is an allusive space where things become other things, where transformations happen in front of our eyes in real time, with real people. It’s a place where stories are told, not just the stories of the narrative but the stories of how the stories are told. It’s a space to explore how as well as what. It’s about recognising the potential of what is in the room: the audience as well as the stage. If you neglect the potential of the audience, then that’s not really theatre. Theatre celebrates and engages the potential of the audience.

PC: What is the potential of the audience?

TC: Theatre is not distinct from everyday life. If a model can be made in the theatre that shows how we are together, how we talk to each other together and how we represent ourselves to ourselves together, then that, to some degree, gives the audience the potential to change the world – in themselves.

I won’t show it to you but you will see it

PC: Looking and seeing is important in your plays. There is the line in ENGLAND, “He’s taught me the difference between looking and seeing.” What is the difference between looking and seeing?

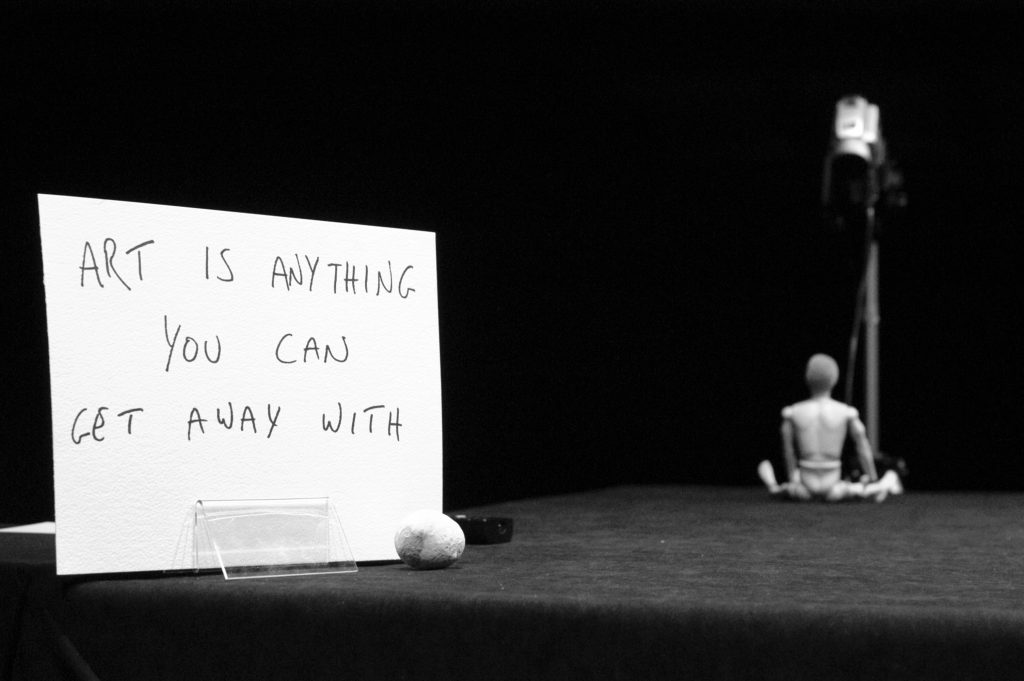

TC: The rubric I have with my work is: ‘I won’t show it to you but you will see it’. I’m not so interested in the spectacle. I don’t think my work is a-visual, but the visual aspect exists in tandem with the internal aspect: the best form of seeing is ‘anti-retinal’ (a Marcel Duchamp phrase). The mind’s eye is an empowering thing. No one can lay a claim to how you see something in your mind. I try to encourage an audience to trust what their mind’s eye sees. This offers a challenge to the material values of the stage. Andy Smith, Karl James and I have talked about what we ‘see’ with our ear: if what the eye sees and what the ear ‘sees’ is the same then it’s a weaker experience. It could be misconstrued that I am looking to reduce the material of the stage to almost nothing, but that’s not my aim. I am not writing radio plays. With Beginners, I still can’t quite believe that I am making a piece of work that has dry ice and flying and props and scenery and physical, material transformation. But I’m using those devices very consciously. They are still there to challenge the dominance of the eye in theatre.

It’s not like I am revelling in some postdramatic wasteland. An Oak Tree, for example, is very much about the essence of performance, of a person being another person and a stage being another place. I say it very directly: you are no longer you, you are this person, here is no longer here, it is this other place. I am always thrilled by the possibility of theatre to transform space, time, people and objects, but I don’t want to do that in a way that is isolated from narrative. Every piece is a dance between narrative and form.

A multiplicity of interpretation

PC: Do you consciously start with collisions of form and narrative or form and form when writing your plays?

TC: I have an exercise that I use with new writers, where they have to write a scene that supports two scenarios. They have to keep both scenarios possible in an audience’s head and if they write something that demolishes one scenario then it’s a failure. The result is a multiplicity of interpretation connected to a narrative. I do this with audiences, actors and objects. For example, the audience is a character in the second half of ENGLAND and throughout An Oak Tree. In Adler & Gibb, the student addresses the character of an audience. In all these instances, the audience and the character of the audience sit side by side.

In Beginners, the characters are both adult and child. The moment the adult actors’ characters achieve transformation they are inhabited and embodied by child actors. That is absolutely right for the play: the transformation not only happens narratively and psychologically, but formally, physically, substantively, structurally.

Play and creativity is an antidote to death

PC: Children and death are common threads that run through every one of your plays. Why do you think they feature in each play and how do they highlight the formal experimentation or formal playing that you do around the mind’s eye?

TC: If we were immortal would we make art? Discuss… I want to challenge the notion of art existing in a separate world. I want to bring it back, and that is perhaps where the children come in. Art is part of a child’s world. Believing that one thing can be something else is how children prepare for their adulthood. As we get older, that process becomes separated, formalised and segregated. Play and creativity is an antidote to death and in Beginners a play is made that defies death.

PC: Where would you say your process fits on a continuum of play to experimentation, with experimentation being the more intellectualised end?

TC: I follow my instincts around form and story.

PC: What is usually your first instinct when starting a play?

TC: The next play I’m working on is rooted in a hunch about what might be possible with a certain configuration of audience, form and story. The first trigger to that play was the thought of an audience reading together. Then, at some point, I found a narrative response to that formal challenge.

I wrote Beginners pretty quickly. I didn’t think too much about it, I never sat down and wrote a map of how all the characters connected. The Author wrote itself very quickly as well. I’m happiest when it goes like this, and so, I think, are the plays.

PC: Do you think that is because the experience is more playful than experimental?

TC: I would certainly see my interrogation of form and narrative as more creative than intellectually experimental: where do these two things meet? where can they meet? how far can they travel? where on the horizon do they meet? Adler & Gibb is a classic example of the form moving forward, then the story racing to catch up and then the story overtaking the form. It just went like that: it’s not because I intended to write an experimental play. Also, everything I’ve written has been in relation to what’s gone before; they are all connected but they feel very different. For example, the idea of ‘letting the nature in’ in Adler & Gibb is important for me, and I go on to explore that in Beginners.

Elements of uncertainty

PC: How do you feel about loose ends?

TC: I try and leave things untied or unfinished, I don’t mean unfinished like “Fuck that, I’m going now.” In their finishedness, there is an unfinishedness. With An Oak Tree, I know the actor will not know the play and will not perform the play how I might once have wanted them to. That is unfinishedness by design, but in the openness around those offers, anything can happen. It is the same with ENGLAND: the audience are active and walking in the first act, and then very present as the woman character in the second. That woman is different every night because the audience is different every night. This thought is developed in The Author. I stress-test these elements of uncertainty, not to see if they will succeed, but to see if the potential for the lack of success will be more interesting than any notion of success.

I don’t think a play should ever be finished, I mean, you write the end, but the process doesn’t end, even after it has met a hundred audiences. Making work that resists commodification or reproduction feels very important.

PC: Finding ways to describe sensation seems important in your work. In Beginners Sandy the dog almost uses the senses to speak, “Sniff, sniff sniff, I sniff your expectations.” There are powerful sensual descriptions that run throughout your plays, do you use them to trigger the audience’s mind’s eye?

TC: Yeah “the policeman walked up the path in silver and he took off his hat at the door in gold.” This is a speech from An Oak Tree, where somebody’s trauma becomes abstracted into blocks of colour.

PC: Great. Why are the senses such a powerful vehicle for thinking together?

TC: I would say emotion is a powerful vehicle for thinking together, particularly in theatre. Perhaps that is what it is, thinking together with emotion: that might be my definition going back to the beginning of this conversation. I think if you can place an idea and attach it to an emotion it is like a rocket booster, it will take you further. All the plays – a man losing his child in An Oak Tree; a protagonist close to death, receiving a heart in England; an abuse of trust in art within The Author – are emotional representations of those ideas. Otherwise you just talk about the ideas, you just write a paper about the ideas. I understand (and maybe I haven’t done so much in the past) how powerful a transporter character can be. I have always been distrustful of character, partly because of notions of character acting, but I have seen in Beginners that characters can be much more than themselves in terms of what they represent about loss, fracturing and family. I want people to believe that these people exist to some degree and emotion is rooted in that of course. What I am doing with Beginners is then complicating that belief because of the way the transformation of those characters is presented.

Wide-eyed with the potential of theatre

PC: Is there a contextual drive for the work that you make?

TC: I’ve not been infected by cynicism about the potential of what could be achieved in this space, about what we can do here, and how complex we can be, whilst retaining love and emotion, character and story. If you are not wide-eyed with the potential of theatre, write for TV.

Read my interview with Andy Smith next.