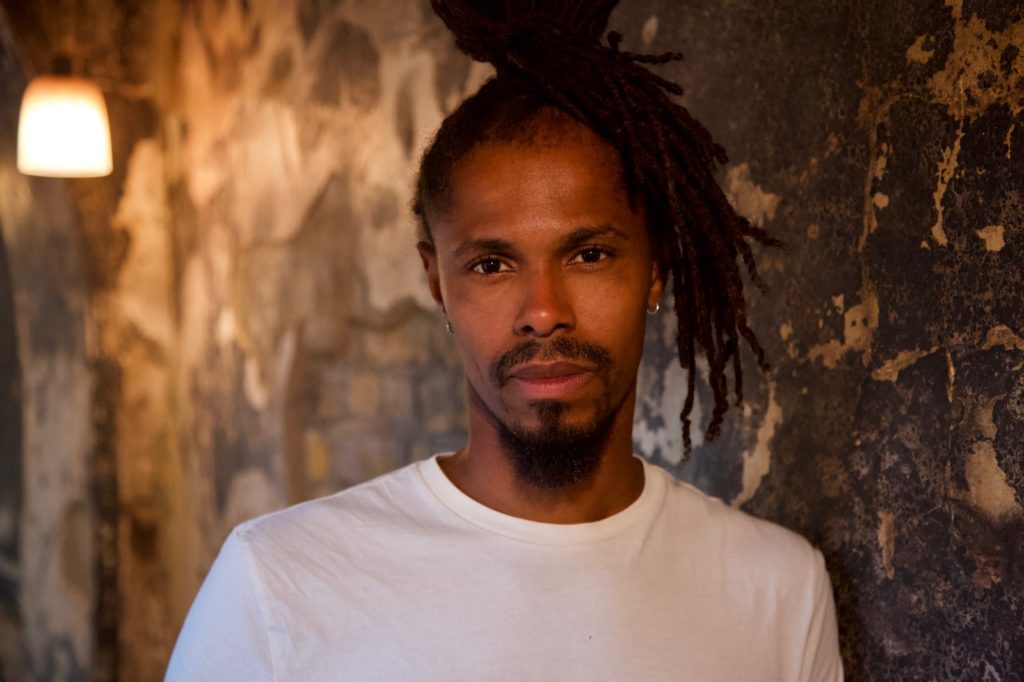

Nicholai is a director and actor who has worked internationally for the last fifteen years. He has acted in Twelfth Night at Nottingham Playhouse, High Heel Parrotfish at Theatre Royal Stratford East, and Mustapha Matura’s Meetings at the Arcola Theatre. He has directed It Had To Be You for Ragoo Productions and Passport to Posterity for Tiata Fahodizi.

Nicholai has worked as the Head of Youth Arts and resident youth theatre director at Ovalhouse Theatre. He directed the award-winning production of Chatroom for National Theatre Connections, as well as site-specific productions of Peter Pan and Ti-Jean and His Brothers in the flower garden at Kennington Park. He recently directed the critically acclaimed production of There is Nothing There at the Ovalhouse Theatre. Nicholai won the prestigious Mayor of London Award for raising the voice of young people and the RSC Complete Works Award for his adaptation of Romeo and Juliet.

He has been the Young Company Director at the Unicorn Theatre in London. and the Youth and community’s manager at Hoxton Hall. Most recently he was Director of Young People and Emerging Artists at the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith. He continues to be Artistic Associate at the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith as he devotes more of his time to freelance theatre directing.

Interview date: 21.01.2020

Clarity and efficiency

PC: What is theatre?

NLB: Theatre is live, communal storytelling. I think it requires a couple of different bits to make it theatre: an audience, a performer, some kind of emotional expression and, as much as post-modernist theatre likes to ascribe a non-narrative structure to things, our brain works in stories, so we’ll always try and apply a narrative to it. I love when people go, “Oh, there’s no story, there’s no narrative.” Okay, cool, fine but I guarantee anybody looking at that thing is going to be trying to piece things together, because that’s how the brain works.

It can happen anywhere, it can happen with any kind of audience, any kind of people, any kind of story, any kind of form or format, once you have a person or people looking at a thing and a person or people telling a thing, that’s theatre, it’s as broad as that.

PC: What is it about teenagers that make them such great theatre-makers?

NLB: They have absolutely no bullshit and they have no tricks. They’re sponges. Brainstorm by Company 3 is a brilliant piece of theatre about the teenage brain. They went and they asked some scientists what’s different between a teenager’s brain and an adult’s brain and the scientists were like, “Yo, a lot!”

Basically, a teenager’s brain is completely different from an adult’s brain – where synapses fire, the bits of the brain that are alive and switched on, the bits of the brain that govern certain things. Very high risk, low consequence, very emotionally live consistently, adrenalin pumping all of the time. Really different. People between 11 and 19 are almost aliens that are trying to exist on an adult planet that tries to apply logic to things but they just don’t fit.

They have no tricks, they’re really honest with how they feel, they’re really honest with who they are, they’re honest about not being able to do something or being able to do something. If you engage with them on a person-to-person level and you’re asking them to do things, you have to be so clear about what your request is and why your request is your request and what the gains are for them and how they can see themselves develop. If you’re not, then you lose them.

The reason why I really enjoy being in a room with them is because the challenge for me is clarity and efficiency. But also, knowing that, as an artist, collaborating with people of that age means that they’re coming at things with such bananas ideas so that the thing that you can come out with is so much more exciting. This is no disrespect to age and legacy and all that stuff, but it’s so much more exciting than a group of people who have been doing it for twenty-five years and they’ve been working in the same way. Teenagers have a much more dynamic thing, much more of an active process about how you do it.

PC: What is your initial response to those big bananas ideas?

NLB: Let’s explore it. Let’s talk about it. I’m not shutting anything down, I want to talk about it, I want to explore it, I want to see where it goes. If it’s big and grand and impossible, let’s talk about it. I don’t want to be in a space where I’m going, practically, we can’t make that work, before we even talk about what it means for the thing.

Time and expection

PC: What are the biggest systemic obstacles to making work with young people and how do you overcome them?

NLB: One of the biggest things is time. Teenagers’ time is not their own, they’re sort of run by the state, they have to go to school, and they have to be home at certain times, which is absolutely appropriate. You have to balance the desire to make something of quality with a real, actual time pressure because their ability to do things, their ability to understand, their ability to take on character or story is absolutely there. If you cajole it in the right way and if you encourage it, you can have beautiful pieces of work.

Historically, in this country, there’s been an expectation that work by young people isn’t very good. That expectation comes from the fact, again no disrespect to anybody, that a bunch of people in the 70s and 80s, all they did was make youth theatre. Over time, they entrenched themselves in an idea of that youth theatre has to be a certain way: it has to be devised and the process is more important than the product and that you have to dumb down because you’re working with inner-city kids. Then, over thirty years, your standards start dropping, you start with this pure idea of how to make work with community groups and young people, but then you end up with this half-baked, half-arsed version of something. There’s also this real arrogance around it and if you tell them any different then you’re just trying to be elitist, applying an adult theory to young people, which they say won’t work. That is just nonsense, that doesn’t make any sense.

The legacy of that is that you go to see a piece of youth theatre and ultimately the first thing they’re doing is apologising for its quality because it’s young people. You’ve seen so many shows where you go in and you can see the set isn’t very good, the lighting is okay and it just has kids standing on stage, the very integrity of the piece is apologising for itself: “We didn’t have enough time and we didn’t make this happen.” No, I think, if you’re smart and you go well, you have a term to make a show, which is only have 14 hours, you go, what can we get in 14 hours? Why don’t you make 15 minutes of something amazing, rather than trying to make 45 minutes of something that’s absolutely shit. That’s what I mean be adjusting expectations, understanding the context and what work you’re playing with.

Since I’ve worked at Ovalhouse, I’ve been making theatre. The fact that it’s with young people is slightly incidental. I expect the same amount of commitment in the room as I would expect from adults. In fact, I expect even more because you’re more energetic.

So that’s another barrier: getting people to take the work that you’re making with young people seriously. We were the first young people’s company at the Ovalhouse to be reviewed by Time Out, we got 5 stars for Romeo and Juliet. That was one of the things that I’ve always driven home, the fact that you can make really good work with these people, but you have to apply a different set of perimeters to get them in the room.

Sensibility and style

PC: How do you judge quality in the work that you’re seeing in the process of making it?

NLB: It’s subjective, so it has to be with your taste but also, I’m a student of theatre, I’m a student of the craft of theatre. In my 30-year career I have seen thousands and thousands of shows and I can tell you unequivocally that the best thing to see is a bad show because it tells you what not to do.

It’s also about testing too. One of the best things for me at Ovalhouse was I got to make theatre. I was pretty uninhibited, if I stayed within budget, I could pretty much make whatever I wanted and for ten years that’s what I did, year after year. I was making three or four shows a year and developing a sensibility and a style for how I wanted to make theatre.

PC: How did your time living and making theatre in Trinidad inform that style and sensibility?

NLB: Totally man, absolutely totally. I lived in Trinidad for twenty years and moved here when I was 20 and I started making theatre when I was 10. That ten-year period was the foundation of everything. I say that I have three dads: my biological dad, who is brilliant and around and then there’s two gay men, both my drama teachers. They were flamboyant and aesthetically aware and understood style and form and feel and tone and colour. So, I grew up around these fashion designers and carnival designers who were constantly thinking about big ideas: Pina Bausch or Aristotle, the way to look at bodies in space and dance and movement and theatre. My idea of how I want things to look and feel comes from those things, comes from those discussions. Then I came here and applied that to a traditional way of making theatre.

Also, I come from a place where I am the majority, there’s tall, skinny black guys as far as you can spit. I come here and I don’t feel like I have to apologise for anything. I have a good friend here, who’s a brilliant human-being but they marvel at how I can walk into a room and get things done. I didn’t grow up thinking that I couldn’t ask for these things or that I couldn’t walk into a room and be in charge of it. I grew up knowing that if I walked into a room and I wanted something I could pretty much come out of that room with it. I still have that, as much as I’ve encountered racist bullshit, I have this doe-eyed way of looking at the world where, all I have to do is be clear about what I want, if I’m clear about what I want, what I want to achieve, what I want to do, I’m going to get it.

Curiosity

PC: How do you go about pin-pointing and releasing the really productive differences in a rehearsal room?

NLB: Curiosity. Fundamentally, if you are curious about yourself, other people and the world that you exist in then that will lead you down some really interesting, beautiful paths because you won’t assume anything. I’m not sat there assuming that I know what someone from Afghanistan has gone through, if I want to understand that, I have to ask questions. I have to ask them who they are at the point that we meet and then not make any assumptions. A big part is then trusting their answers too.

PC: How do you combine that spirit of listening with your own artistic ideas?

NLB: I think in pictures, right? So, when I’m making a show, the first thing I do is make a pinterest board, because I want this to feel like this, a picture of a woman on a beach that sparks something, that is how a play should feel. Then I go to a museum and walk around and be like: Is that the thing? Is that how it should feel? Is that the emotion that wants to come out of me? It’s sort of an amorphous cloud that is bubbling around me. Then when I get in a room, I know how I want it to feel, but how we get that is a collaboration, so I ask questions.

PC: How do you approach a rehearsal room on day one to ensure that it is a space where people feel confident to answer those questions?

NLB: It’s really super-important that everybody gets a chance to be seen, it’s just little things: I call people’s names: “Ahh, Phil that was wicked.” Or “Everyone, look what Phil did.” Or “Everyone, pause for a second, Phil you do that thing.” Or “What do you mean? Let’s take a little longer with that.” That might not be necessary for the process and it might mean that we take time over something that might not end up in that piece, but it does mean that everybody in that room has had a chance to be present and to feel seen and to say something and to feel like they led something.

It’s also about listening to what people aren’t saying, the energy in the room. I try to bring everyone in. Equally, doing the opposite of that too, if somebody is trying to be too dominant in the room, I might ignore them for a little bit – I see, and I hear everything.

The next thing I’m doing is I’m consciously lowering my status by making jokes, by pretending I can’t do something. I play charades at the end of each day and I actively say I’m not allowed to play this game at home or with my friends because I’m a monster. I’m loud, I’m a sore loser and when I win, I literally go bananas and I lord it over everybody. I say this at the start and then I become this weird, bananas person inside of the charades game and they’re laughing at me while we’re playing. What that does is, all of a sudden, I’m approachable, I don’t have to have all the answers in the room, we can do things together, somebody else is smarter than me, these 14 year olds are much more sensible than this 40 year old yahoo who’s shouting stupid guesses. Then we come back the next day and we warm up for twenty minutes and all of a sudden, the balance is back there. I’m shifting and changing that status all of the time.

Ask questions

PC: What is the change that you want to see?

NLB: I want there to be more space for everybody’s story to happen. That’s getting better, it’s getting there, but it’s not fast enough. For the better part of my time in this country there’s been a real propensity for one kind of story and a set of people dominating who gets to tell a particular kind of story. I, as a human being, cannot understand the breadth and depth of the world that I live in if I only hear one story. I will go to that place and see a particular thing and then I’ll come outside and the world that I live in is completely different. Art should be the mirror of our society and it should make us ask questions of ourselves but we’re only asking questions within a very tight framework. Who does that serve? It tends to perpetuate a very singular narrative and so it perpetuates people believing a thing about themselves that ignores swathes of the world. Our society is changing, multicultural, multi-ethnic and bi-racial. That has to be represented on our stages, but it has to be represented in a non-elitist way.