Here is a selection of places to ignite your imagination.

All images are sourced from ukfilmlocation.com

Thinking together about theatre

This week we take a look at a range of ‘devising’ theatre companies. We have used the companies featured in The Contemporary Ensemble: Interviews with Theatre-Makers edited by Duška Radosavljević and Devising in Process edited by Alex Mermikides and Jackie Smart. This can be a visual accompaniment to these fantastic books.

In this interview Grzegorz Bral director of Song of the Goat Theatre and LSPAP talks about London School of Performing Arts Practices, Brave festival, coordination technique and his approach to theatre and performing arts.

By Adriano Shaplin

Directed by Rebecca Wright

Performed by Kristen Bailey, Drew Friedman, Adriano Shaplin, Mary Tuomanen, Stephanie Viola

Set by Caitlin Lainoff / Lights by Maria Shaplin / Costumes by Katherine Fritz / Sound by Adriano Shaplin

Performed at Incubator Arts Project, May 2012, NYC

“Delicately hilarious…a clear-eyed ethnography of our own species at a specific developmental stage…the ensemble seems exquisitely tuned to a difficult chord of poignancy and awkwardness.” –Time Out

SOPHIE 5-18-12 MASTER H264 1280×720 from The Riot Group on Vimeo.

By Adriano Shaplin

Directed by Whit MacLaughlin

Performed by Drew Friedman, McKenna Kerrigan, Jeb Kreager, Mary McCool, Paul Schnabel, Adriano Shaplin, Stephanie Viola

Lights Maria Shaplin / Costumes Rosemarie McKelvey / Sound Whit MacLaughlin / Projection Design Jorge Cousineau / Production Stage Manager Emily Rea / Executive Producer: New Paradise Laboratories

Freedom Club was made possible with the support of Princeton University, Drexel University, the Off-Center for Dramatic Arts, the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage through the Philadelphia Theatre Initiative, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

“Epic theatre…possessing a unique, violent, and total language, at once written, spoken, and played.” –CultureBot

“In Freedom Club the darker underpinnings of human liberty are considered with a grim cackle.” –The New York Times

“A daring mashup by two experimental companies (Philadelphia’s New Paradise Laboratories and New York’s the Riot Group) and two eras (1865 and 2015), “Freedom Club” indicts fanatical radicalism in America. Aptly self-described as “a hallucination on national themes,” the satire vividly skewers self-aggrandizing extremists from John Wilkes Booth to a feminist collective that spawns another presidential assassin.” -Variety

Freedom Club from The Riot Group on Vimeo.

A short documentary about The Neo-Futurists and their long running late night show Too Much Light Makes The Baby Go Blind. Contains clips from the show and interviews with, Jay Torrence, Heather Riordan, Caitlin Stainken, Greg Allen and others. The Neo-Futurist are a Chicago based theater company who produce the longest running show in Chicago, T.M.L.M.T.B.G.B. (30 plays in 60 minutes) , as well as a full season of original primetime shows.

History oktober 2014 deel 2 from Ontroerend Goed on Vimeo.

ALL THAT IS WRONG – FULL PLAY from Ontroerend Goed on Vimeo.

Tom Nicholas caught Ontroerend Goed’s £¥€$ (or Lies) at the Drum Theatre this week ahead of its transfer to Summerhall and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. This interactive piece by the Belgian provocateurs sees the theatre transformed into a casino and audiences into freewheeling free market capitalists. Here’s Tom’s performance analysis of the show.

Tom is an exciting theatre vlogger putting out interesting new videos every week discussing theatre and playwriting from the perspective of an aspirant and (some might say) emerging playwright, theatre maker and academic. Support this fantastic tool with a subscription.

Twitter: @Tom_Nicholas

Website: www.tomnicholas.com

People Show 121: The Detective Show from People Show on Vimeo.

Julian Maynard Smith is the founder and artistic director of Station House Opera. Founded in 1978, Station House Opera creates solo and group performance work as well as sculpture and installation. Dissolved is the company’s first new work since the city scale site specific project Dominoes in 2009 and follows earlier intercontinental performances developed as far back as 2004. Their distinctive engagement with audiences crosses new boundaries with an installation and performance that uses live video streaming to dissolve spaces in London and Berlin, bringing people from both cities into dynamic connection.

dissolved (extract) from julian maynard smith on Vimeo.

Station House Opera – Snakes and Ladders from julian maynard smith on Vimeo.

Station House Opera – Mind Out from julian maynard smith on Vimeo.

This is Theatre O’s vision statement. Rather than just have something written down on a piece of paper, they thought it would better to reflect how they approach work by making something a little more visual. They worked with animator and long term collaborator, Paddy Molloy, who made a stop frame animation of the creation and destruction of a drawing he made based on our previous work.

Vision from theatre O on Vimeo.

Delirium Trailer from theatre O on Vimeo.

The Argument – Car Crash from theatre O on Vimeo.

The Argument – On Old Age from theatre O on Vimeo.

Gecko Compilation 2015 from Gecko Theatre on Vimeo.

About Gecko | Education from Gecko Theatre on Vimeo.

Amit FAQs | Education | Gecko from Gecko Theatre on Vimeo.

FAQs for a Gecko Performer | Education | Gecko from Gecko Theatre on Vimeo.

Third Angel have always worked with rules when making shows, and they’ve always enjoyed the creativity that those restrictions give us – as well as enjoying the moment when you realise that the rules need to be broken. Popcorn is a performance for both camera and live audience reflecting on rules, time, making stuff, shared language, shared history and friendship. Performed and filmed on location at The Holt cafe and art-space, Sheffield.

Third Angel: POPCORN from Third Angel on Vimeo.

“Although many stories have been adapted from written sources. rakugo can be considered a genuine form of oral art because its principal route of transmission down to us has been through the lips of the performers. To this day there are no written manuals or librettos containing the full text of a performance or of the way a story has to be presented. There is mainly oral transmission from master to pupil. Written notes to help in memorization or tape recordings are frowned upon. Through long years of personal association with his teacher, listening to his performance from backstage, and living as an apprentice in his home, the student devotes his attention to mastering the stories.”

“The sense of reality is maintained throughout the story, and shared by performer and audience alike. Drawing freely on his personal experience, the performer styles his own individual pre- amble or “pillow” (makura t) for his story, selecting among con- temporary events, the weather, or work, whatever topics he feels his audience might be interested in. When he enters into the story itself, then his hero, in a curious and sudden shift of time dimen- sion, leaps out of the setting of an old tale right into the present moment and confronts the audience. Here, if the storyteller clumsily tries to evoke laughter in an obvious way, the effect will amount to nothing more than crowd-pleasing titillation, and his story may fall flat. But the expert performer can bridge the time gap smoothly and without a hitch, drawing the audience along with him into the world of classical rakugo.”

“The rakugo performer must organize his story in a new way each time, but if he is to remain within the confines of classical tradition, he is forced to observe certain definite rules. Throughout several centuries of rakugo the main plots of the stories and the heroes’ names have not changed. In the organization and minute descriptive details of episodes, with each performance, each year, and each generation, a great variety of different nuances and changes have appeared. No story can ever be performed twice in exactly the same way.”

“Changes in scene of a story are described by onomatopoetic words and sounds; for example, the ringing of a temple-bell, bon-bon; the clatter of wooden clogs, karan-koron; the sound of the wind, pyiu u u u; rolling of stones, gara-gara; or noise in the background, di-di, go-go. Onomatopoetic insertions can extend over a period of more than one minute, when they describe such movements as slow walking, tata tata…, tsun tsun …; running, sai-sai koro-sai, e-sa-sa, sowa- sowa, chowa-chowa; walking with heavy baggage on one’s shoulders, wasshoi-wasshoi…, or the sounds of work and play, kachi-kachi, pachi-pachi, pochi-pochi, poka-poka, potsu-potsu, sara-sara; or heavy exertion, hora-yo, sora-yo,yosshoi.”

“The rakugo performer is not supposed to change his position once he takes a seat on the stage. But merely by the movement of the upper half of his body he represents all kinds of actions. Walking from one place to another is expressed by one of the most amusing gesture formulas of rakugo: the performer withdraws his hands into the wide sleeves of his kimono, his knees, hips, and shoulders sway rhythmically, and he talks to himself in a murmuring voice, as if lost in thought. The audience knows that a person is on his way to an- other place; they also know that he will suddenly be startled out of his thoughts by an unexpected event, and they anxiously wait for that moment.”

“The focal point of the rakugo story is the world of everyday. Many of its cast of characters strut about dressed in sundry garb and historical costumes, but they are part of the storyteller’s world and the world of his audience. From there the rakugo performer takes the models which he fits into various stereotypes according to class and profession: the feudal lord, the military man, the priest, the scholar, the retired head of the house, the working-class man, the farmer. At times the principal characters are complete outsiders that do not fit into ordinary societal roles: the cheapskate, the thief, the liar, or the prostitute. Sometimes it is just the simpleton, the lazy- bones, the miser, the boozer, and the conniver that pass across the imaginary rakugo stage. There are, of course, no detailed portrayals of people as individuals. This is the major difference between rakugo and pure literature. While there are instances where a character is provided with a definite personality, there are practically no examples of that personality changing as the story develops.”

Here is a selection of soundtrack music that I hope will be a good stimulant for your week.

On the southern coast of India, the three-hundred-year-old Kathakali ritual theatre still flourishes, a mixture of dance and pantomime, religious inspiration and mythological tradition.

The plays describe extraordinary events involving gods, demons, and legendary characters. They all have one common characteristic: good and the gods always triumph over evil and the demons. The actor acts out the struggle between good and evil exclusively through the motions of his body, and the subjects of the plays are as well known to the audience as the myths of the Greek trilogies were to the Athenians.

Through his gestures and his mimicry, the Kathakali actor recreates the atmosphere and the action of the drama while describing to the audience the action’s locale. His technique is much closer to the Chinese opera than to the European mime or ballet, which tells a story through a direct or “exoteric” technique. In the Oriental ballet, on the contrary, a cipher is used. Each gesture, each little motion is an ideogram which writes out the story and can be understood only if its conventional meaning is known. The spectator must learn the language, or rather the alphabet of the language, to understand-what the actor is saying. This alphabet of signs is complex. There are nine motions of the head, eleven ways of casting a glance, six motions of the eyebrows, four positions of the neck. The sixty-four motions of the limbs cover the movements of the feet, toes, heels, ankles, waist, hips-in short, all the flexible parts of the body. The gestures of the hands and fingers have a narrative function and they are organized in a system of fixed figures called mudras (“signs” in Sanskrit). Those mudras are the alphabet of the acting “language.”

The face expresses the emotions of the actor. If he is terror-struck, he raises one eyebrow, then the other, opens his eyes wide, moves his eyeballs lathis nostrils flare out, his cheeks tremble and his head revolves in jerky motions. To express paroxysmal rage, his eyebrows quiver, his lower eyelids rise on his eyes, his gaze becomes fixed and penetrating, his nostrils and lips tremble, his jaws are clamped tight, and he stops breathing to bring about a change in his physiognomy. There are sets of facial motions to express not only feelings and emotions, but traits of character of a more permanent nature, such as generosity, pride, curiosity, anxiety in the face of death, etc. However, the actor does not rely exclusively on prearranged mechanical gestures to express emotions. He cannot reach his audience unless his own imagination and motions come into play. The old masters of the Kathakali have a rule which says:

“Where the hands go to represent an action, there must go the eyes; where the eyes go, there must go the mind, and the action pictured by the hands must beget a specific feeling which must be reflected on the actor’s face.”

From this rule we can see that the face is the emotional counterpart of the story told, not by somebody else, but by the actor’s own hands. In short, there is a double structure: the actor must resort simultaneously to two different sets of technique to express the two complementary aspects of a story, the narrative and the emotional. His hands “tell” the former, while his face expresses the latter.

The BBC’s Megha Mohan went to a now-closed traditional Kathakali school, one that gave birth to its own style, the Kalluvazhi Chitta: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-asia-india-35473499/a-rare-performance-of-india-s-kathakali-dance

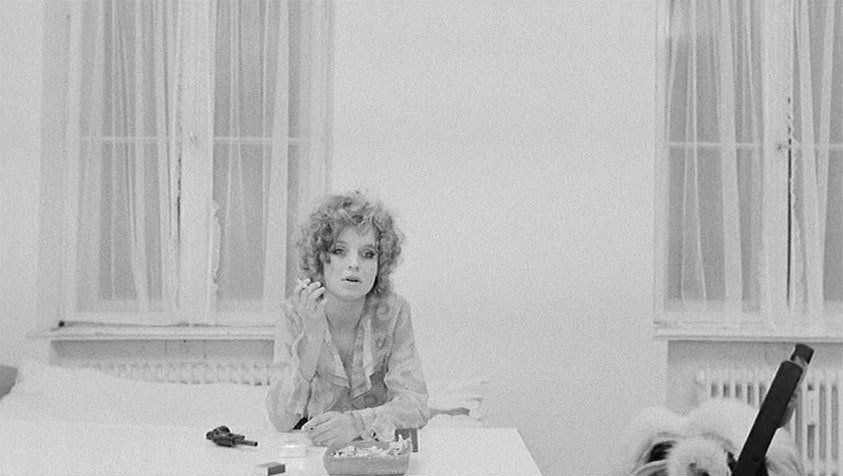

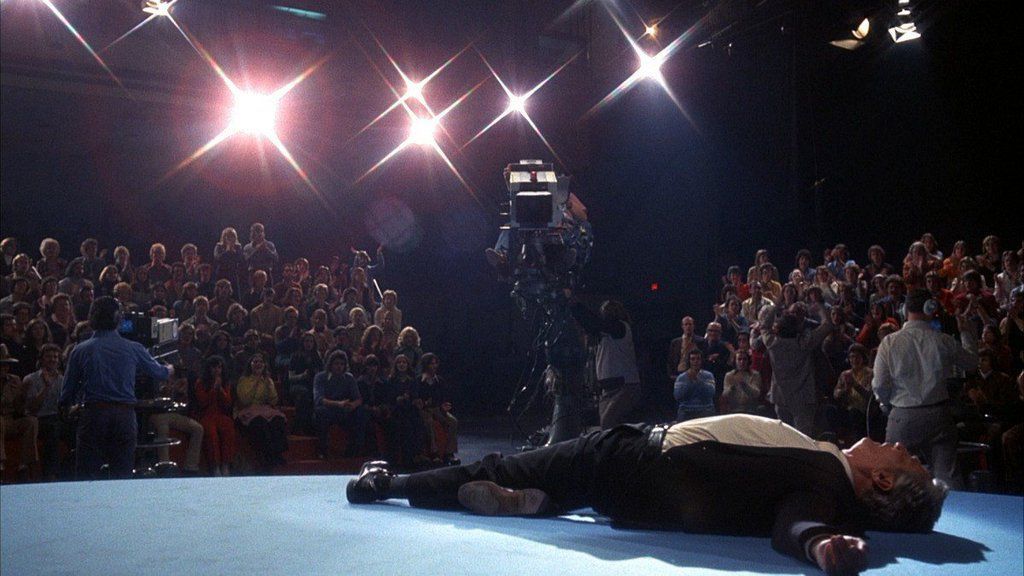

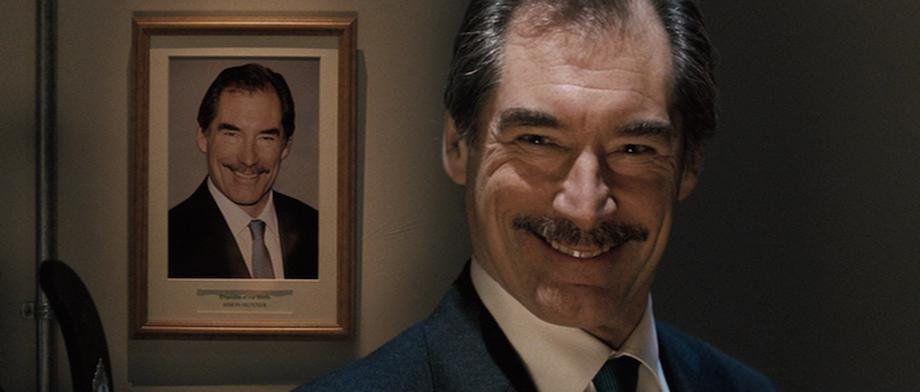

Do you need stimuli for your devising work? Inspiration for a design? Here are a selection of still shots from films courtesy of the fantastic Film School Rejects’ Twitter account @OnePerfectShot

Share your ideas with us on Twitter or Facebook.