Suggested Donation

Bertrand Lesca is a theatre maker from France. After studying at Warwick University, he went on to assist Peter Brook and Declan Donnellan on several international tours. Bertrand currently works with Nasi Voutsas (Bert and Nasi) with whom he co-created the trilogy EUROHOUSE, PALMYRA and ONE.

The Frame

PC: Your work seems to fit into a long tradition of comedy double acts, was that a conscious decision?

BL: No, it was more about understanding the dynamic between us two. We quite quickly found, whilst improvising, that I was oppressing Nasi and he was just the victim of this horrible person that I was playing. We always found it very amusing and very funny. We had no sense that this was what we wanted to do, it just kind of started to happen. Then we saw the film of Bloody Mess by Forced Entertainment which had a comedy routine that was happening between two people where one clown wants to put a line of chairs to the front of the stage and another clown wants to put the chairs to the back. It starts with just one man starting to place them and then the other one moving them and then the way that it builds was really amazing. There was something almost political about it but again not naming anything political: just two people on stage wanting different things. We were really interested in what you could read into that if you give that scene a title. If you frame it for the audience, you start seeing the scene differently.

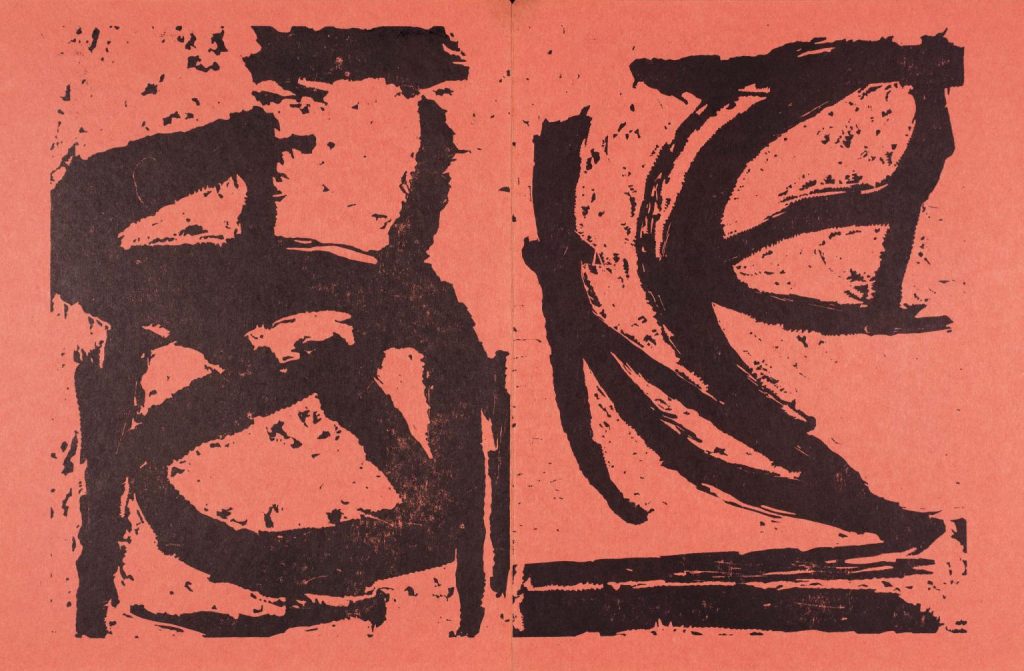

I think that idea of framing something is quite key to our work. Something clicked, as well, when looking at Cy Twombly’s paintings. Even though his art is very abstract and hard to decipher, there’s always a title which comes to support the viewers understanding of what it’s about. We always try and give our work a very clear title, a very clear frame so that we can take the audience on a journey.

PC: What’s the first thing that you do when developing a piece?

BL: We get into the room and we just start talking about this thing. Then at some point we need to stop talking and start making something. We then try and leave all the information that we’ve gathered together outside and we start playing. Usually there’s just the two of us, so we start playing games and running long improvisations that carry on for anything up to an hour and a half. After that we make notes of things that we’ve found during the improvisation and what connected to the ideas that we’ve talked about. But we have to find the game and what the game is. So, if you have a man on the ladder and you have a man who’s not on the ladder, what’s the game? How can you play with that? We take a long time to work out what games work with the particular political context that we’re exploring. At the end of the day, it needs to be something that we can play, that we can act with. If it gets too complicated we usually leave it to one side.

PC: Are those connections always clear?

BL: We try to make them clear but sometimes there’s a sense that the meaning of it even escapes us, we don’t really know why it works but we think it works. For example, in Palmyra there’s this moment when I start shaving Nasi’s beard with the microphone, there’s something so violent about this but also very playful, but the meaning of it didn’t come through the first time, we were just playing. It came up again and it was very clear for us that it was about how people perceive the beard of a Muslim person and the act of shaving it, it’s offensive from a religious point of view but also a really quite aggressive thing to do. That all started off as a game; something completely unconscious that we did in rehearsals which came back again and made complete sense with what the show also needed to say.

Read the full interview here.