Suggested Donation

This is an extract from an interview with Tim Etchells, Artistic Director of Forced Entertainment – read the full interview here.

Again, it’s about the relation to the spectator. Perhaps theatre has in it this idea of the spectator who passively consumes or watches something in a distant way – consuming the events as they unfold in front of them on the stage as if your responsibilities to the theatrical event are not much more than being entertained or keeping track of what’s going on down there in the dark. The witnessing idea arises from a desire to go beyond that – to make that relation between the spectator and the stage more complex ethically and politically.

Brecht talked, in that poem about the street accident, about the idea of the witness and the guy who’s explaining how the car went this way and the other car went that way. The explainer in that poem has the responsibility to get it right because it matters. Who crashed into who? Who’s fault was it? How did the guy got knocked down? So there’s something about witness that’s about being truthful.

You also have somebody like Chris Burden who in his 1971 piece Shoot is shot in the arm by his friend in the gallery. He talked about the people who were there that night for the performance as witnesses rather than spectators. That’s to stress the reality of the thing that happened – a bullet going into an arm. Burden says that watching that is different from watching a fake bullet fired from a fake gun – there’s a quality of “realness”.

We’ve done nothing with that kind of bold claim on ‘reality’ but I think we’ve always tried to look at the stage and the auditorium and how to implicate the spectator in a more complex way.

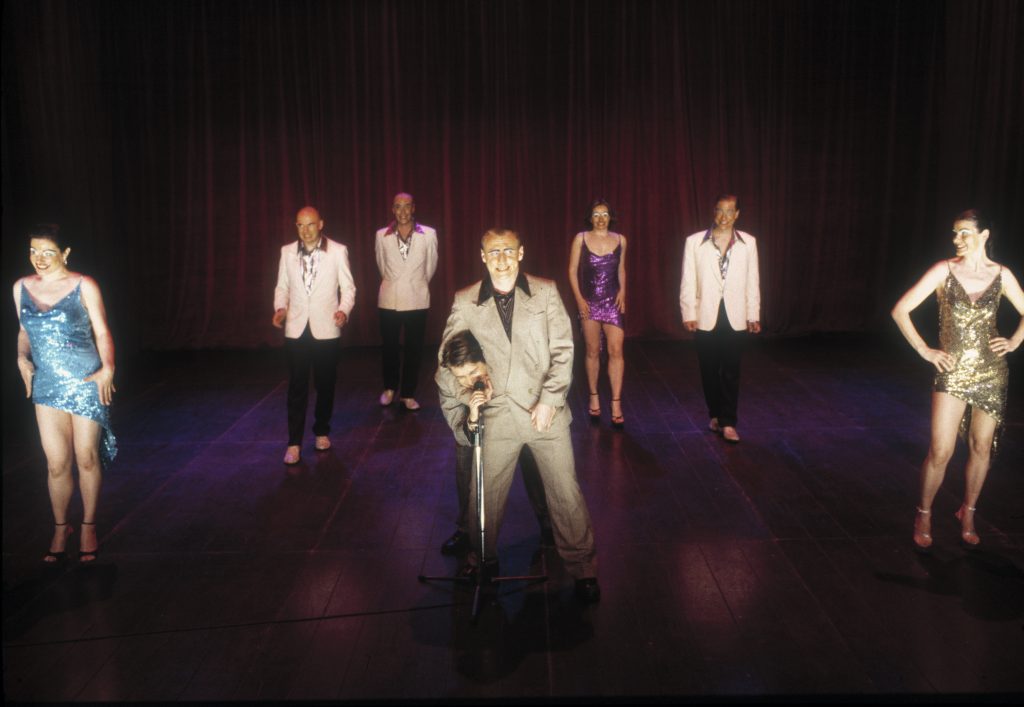

We make work that refuses to be simply an entertainment taking place at a distance, down the other end of the telescope, down there on the stage. Instead we try to find ways to triangulate the work directly to the auditorium. As if to ask the audience who they are and who is sitting with them, to wonder not about the narrative of a drama but about the truly present situation and dynamic of the theatre. So many of our shows ask that question in different ways. Often we have worked by creating a kind of dramaturgical tension in the auditorium or between the stage and the auditorium. For example, in First Night the performers appear as rather failing vaudevillians or nightclub entertainers who effectively turn on the audience in different ways – vague insinuations and then direct attacks, the surface of the entertainment crumbling. “It’s all good people here; there’s no racists here; there’s no homophobes here; there’s no wife beaters here.” Taken together it creates a kind of probing of the audience, forcing them to take a position, to think about who they are and who the strangers in the seats nearby might be. Theatre perhaps sees itself for the most part as a gathering of the good, honest and true to watch something that will enlighten them. A benign, convivial space. I think, a lot of the time, our work wants to niggle at that, transforming it into this unfolding set of ethical and political negotiations with the audience which connects to this idea of witnessing. Something is at stake.