Interview with Paul Allain

Paul Allain is Professor of Theatre and Performance and Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Kent, Canterbury. Since collaborating with the Gardzienice Theatre Association from 1989 to 1993 he has gone on to write extensively about the theatre. He has published several edited collections on Grotowski as part of the British Grotowski project.

Paul’s films about physical acting for Methuen Drama Bloomsbury will be published at Drama Online in Spring 2018 as Physical Actor Training – an online A-Z. Draft films are currently available at the Digital Performer website.

email: P.A.Allain@kent.ac.uk

Connections to the IB, GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- theatrical style

- innovations

- key collaborations with other artists

- relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

- significant moments in the development of theory and practice

Images of productions can be found at grotowski.net

PC: How long was Grotowski working as a director?

PA: He wasn’t a director in the traditional way that we would understand someone who just produces a repertoire of work. That was a period of fifteen years: from studying in Moscow, then traditional drama school in Kraków and then setting up the Theatre of Thirteen Rows in 1959. He created his very last performance in 1969. It is a very short period of making theatre performances but they astounded the world and completely transformed our understanding of what theatre can do.

PC: What was the sequence of the most significant productions?

PA: It was The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Akropolis, The Constant Prince and then Apocalypsis cum Figuris.

PC: Was Dr Faustus the only text he worked with?

PA: No, all his other performances were based on classical texts but not just classical as in our canon in Britain, Western Europe or America. They were based on Polish and in one case a Spanish classic. This is something people mistake about him; they think that he was devising and creating these texts, but in fact they were mostly well known and classic Polish dramas. Some of them were fragmentary poetic dramas.

PC: Why was Dr Faustus significant?

PA: In 1962, Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe was reframed as the last supper where the audience are invited to see Faustus in his last hour before he gets taken away by Mephistopheles. Dr Faustus pushed the actors’ work a long way. It launched Grotowski on the world stage because it was the piece that Eugenio Barba saw and took visitors and producers to see at an International Theatre Festival. The actor/spectator relationship in the space was crucial as it was in all his productions. In Dr Faustus the spectators sat at a table with the action happening on this table at chin height, right in front of their faces. Rather than looking at the back of someone’s head, as you would do in a proscenium arch theatre, you were looking at another spectator also experiencing the same things. This very much amplified the experience.

PC: What about Akropolis?

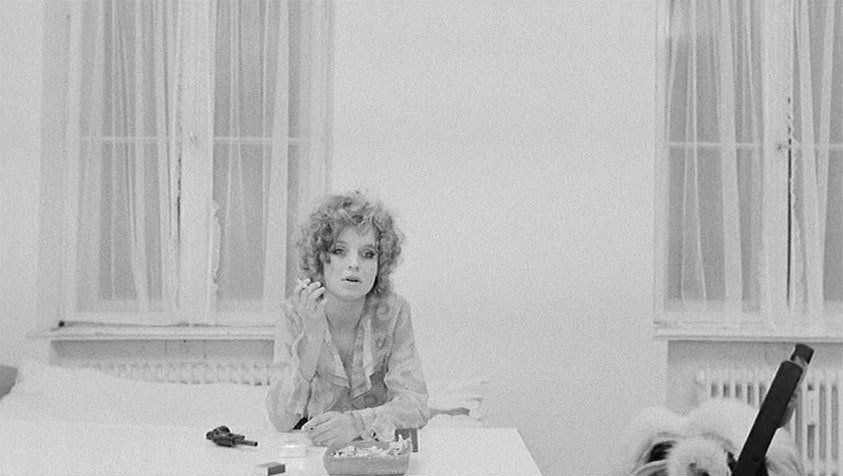

PA: It was made in the same year as Dr Faustus, 1962 and there is the film record of it, even though it is not a very good rendition. It is more of an ensemble piece based on the classic play by Stanisław Wyspiański. This play was originally set in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków, which is the national cathedral where these dead kings and queens lie in state. Grotowski relocated it to Auschwitz. It was a very important production for addressing the Holocaust, being set in Kraków, thirty miles away from Auschwitz itself, just seventeen years after it was liberated. They developed this whole mise-en-scène where the concentration camp was built around and above the spectators during the course of the performance. They were surrounded by the action and at the start of the play they were told, “You are the living and we are the dead.” The spectator was positioned as a witness again.

PC: You touched on The Constant Prince earlier. Why was that a significant production?

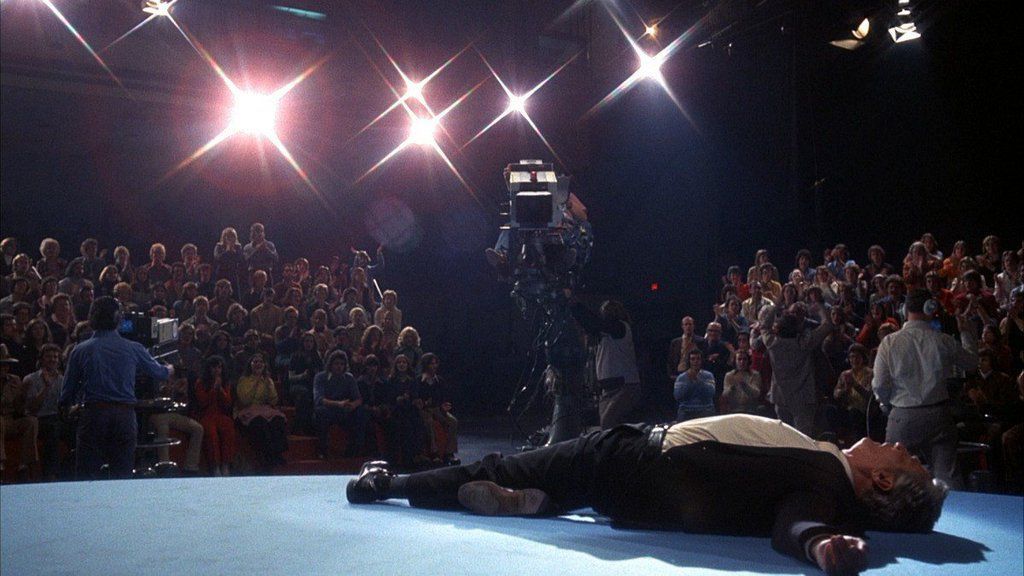

PA: The Constant Prince followed in 1965 and is seen as the production where Grotowski’s acting techniques got taken to the highest level. It was Cieślak’s total act as the Constant Prince, this gift of himself: the holy actor. Critics couldn’t articulate their experience easily but they talked about Cieślak’s illumination. The extraordinary nature of what he did comes across even in a grainy film, shot with one camera. It is a bad rendition but the embodied sense of what it might have been like to be a spectator there comes through. For this production, the spectators were positioned above the stage, watching this actor enacting this repetitive ritual of torture, being asked to give in and yet not giving in, delivering this poetic response about why he would not do so, why he is constant. The high position of the spectators meant they are put in this awkward place: if they sit back in their chair they can’t see the action so they have to lean forwards to observe someone’s suffering. They are put into this position of being a willing voyeur in someone else’s suffering.

Full version available here

PC: What about his final production?

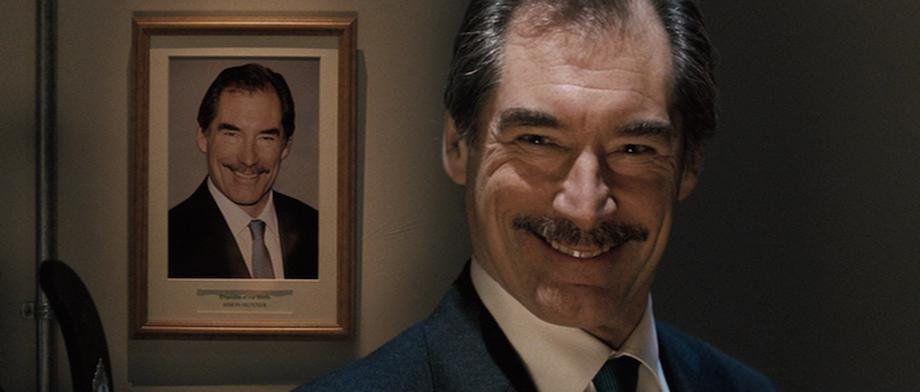

PA: Apocalypsis cum Figuris (1969) was his last performance which he carried on presenting until 1979. It stands out for many reasons. It overlapped with the paratheatre phase. People would often come to the performances, stay behind afterwards and talk, then get invited to participate in paratheatre. It was devised, as we’d call it today; they took texts from T.S. Eliot, Simone Weil, from The Bible. The production was heading away from theatrical structures. The first version was in costumes, then Grotowski said, “No, wear your daily clothes.” Initially there were benches for the audience, then they removed them. It was performed in an empty room, getting back to that simplicity of just people in a space. The distinction between the spectator and the actor was being blurred. That interaction, that encounter was then extended into paratheatre, where there were no spectators, no observers, just actors.

Up Next:

Part 5: Grotowski and Gurawski: Configuring the Space

Part 6: Grotowski Inspired Creativity and Outrage

Part 7: Grotowski’s Work with Text

Part 8: Grotowski’s Communication with Spectators

Part 9: Acting for Grotowski: What is it to be Human?

Part 10: Grotowski Composes Associations: Plastique and Corporal Exercises

Part 11: Grotowski’s Voice Work: Connecting Body and Voice

Part 12: Grotowski’s Context: Sickness, War and Oppression

Part 13: Paratheatre: What is Beyond Theatre?

Part 14: Paratheatre: Finding the Desire to Change

Part 15: Grotowski’s Influence: Barba, Brook and Beyond