David Barnett is Professor of Theatre at the University of York. He works mostly on German theatre, with a particular interest in the Brechtian tradition of making theatre politically. He has written widely on postdramatic and experimental theatre, play texts and directing.

David has developed a wonderful free-to-access resource that connects Brecht’s theories for the theatre to real-world theatre practice. Brecht in Practice is aimed at people who are interested in the political possibilities of theatre-making, who may have read about Brecht and his ideas, but who might find the gap between theory and practice hard to bridge.

The site complements David Barnett’s book, Brecht in Practice, a volume in which many of the theoretical issues are discussed in greater detail.

David has kindly shared a taster of the vast content from Brecht in Practice. This simply scratches the surface of the site and we urge you to follow the links and take full advantage of this fantastic free resource.

Brecht in Practice is rooted in theory but each theoretical idea is connected to real examples in order to show the relationship between theory and practice.

Who was Bertolt Brecht? an overview of Brecht’s life and ideas

Brecht (1898 – 1956) experienced a turbulent world first-hand and sought to understand how such instability could occur and how his approaches to theatre might represent a dynamic, active world that was also capable of change.

The Meaning of ‘Brechtian’: a definition of what this term might mean for theatre practitioners

‘Brechtian’ can be found in all sorts of contexts and applied to all manner of theatre and performance. It is often used to describe certain devices used in performance, such as direct address to an audience, the use of placards or signs, or showing the mechanics of a production instead of hiding them behind illusionist aesthetics. In the light of this, one could describe all manner of TV adverts as ‘Brechtian’, but it is obvious that none of them are concerned with criticizing capitalism or its excesses – on the contrary, they are designed to increase consumption and profits.

I thus propose that ‘Brechtian’ implies the dialectical examination of dramatic material. That is, ‘Brechtian’ puts the emphasis on a method of dealing with dramatic material, not necessarily the means with which the material is performed, even though they are important. While ‘dialectics’ is a philosophical term and has its own vocabulary, the process of dialectical examination is based on the search for socially contextualized contradictions. The theatre company then looks for suitable ways to perform the contradictions in a theatre of showing.

In short, a focus on Brecht’s means rather than his aims can de-politicize the theatre, and make it purely the site of entertaining devices rather than one that engages with society and its mechanisms with a view to changing both.

The Aims of Brechtian Theatre: gives an overall introduction to what Brecht was trying to achieve in his theatre and how he set out his theoretical ideas.

The list of points below is not exhaustive, but does draw attention to some of the more important aspects of Brecht’s theatre.

To stage accurate representations of human beings

To reveal the social factors the influence human action, behaviour and thought

To show the (stage) world as changeable

And derived from these ideas, a Brechtian theatre seeks to:

- Criticize human behaviour, actor and thought as ‘natural’

- Articulate contradictions clearly

Brecht’s Aims for a Production:

Brecht’s Means:

The Brechtian Method: outlines how Brecht’s approach to making theatre can be considered a ‘method’ and how it might be applied.

It begins with the construction of the Fabel , which then leads to initial blockings in the form of the scenes’ Arrangements . The actors then develop a basic Gestus for their figure, and inductive rehearsal leads to a diverse range of Haltungen . The aim, as ever, is to produce lively, realistic theatre that allows the spectator to speculate on the ways society works by drawing attention to the contradictions that drive the action.

A Theatre of Showing: Brecht’s theatre is all about setting out relationships with clarity and not passing over contradictions

Theory and Practice: considers the relationship between the two and offers thoughts on how the two can be negotiated.

Marxism, Dialectics and Contradiction : a more detailed discussion of Brecht’s approach to reality with an emphasis on how the world works and how it can change.

Brecht’s Approach to Reality : this relationship lies at the heart of Brecht’s theatrical ambitions and differentiates his theatre from other forms of theatre-making

Brechtian Realism: contrasts the more conventional definition of ‘realism’ in the theatre with Brecht’s

Politics in a Brechtian Theatre : what are the political implications of Brecht’s theories?

Making Theatre Politically: what is the difference between ‘making political theatre’ or ‘making theatre politically’?

Modelbook

Brecht in Practice presents a virtual modelbook based on a production of Patrick Marber’s Closer.

Click here to access the Virtual Modelbook of Patrick Marber’s Closer.

Patrick Marber’s Closer

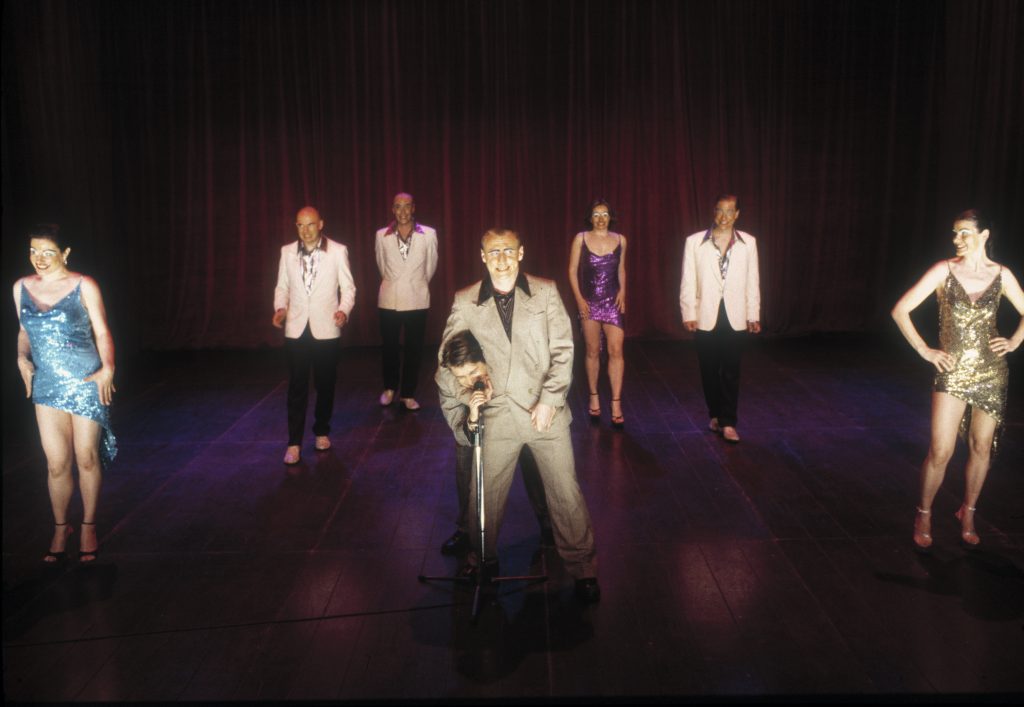

Brecht in Practice takes an in depth look at a production of Patrick Marber’s Closer staged at the University of York with professional actors in October 2016. The site provides a detailed analysis of the production from the starting point of the theory introduced.

Free resources to download

You can download the following exercises:

- Social Salutations – a simple exercise with a couple of variations that establish Gestus and Haltung, and introduce Brecht’s theatre of showing .

- Posh Restaurant – a scenario that invites participants to think about class, not through character, but through a clear situation and a series of relationships. The scenario further develops Brecht’s emphasis on showing material onstage and sensitizes participants the processes that lead to actions and reactions in public.

You can also download the following approaches to working with dramatic material:

- The Role of the Fabel – this plan introduces the practice of writing a Fabel for a scene and staging material in its light. You will also need to download this extract from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and this sample Fabel .

- Inductive Rehearsal – this plan introduces the practice of inductive rehearsal , a method Brecht developed for actors working with issues of social status and the pressure of social situations.

Want more on Brecht? Read our interview with Professor Tom Kuhn here.