Extracts from Rakugo: Popular Narrative Art of The Grotesque by Sasaki Miyoko and Morioka Heinz

“Although many stories have been adapted from written sources. rakugo can be considered a genuine form of oral art because its principal route of transmission down to us has been through the lips of the performers. To this day there are no written manuals or librettos containing the full text of a performance or of the way a story has to be presented. There is mainly oral transmission from master to pupil. Written notes to help in memorization or tape recordings are frowned upon. Through long years of personal association with his teacher, listening to his performance from backstage, and living as an apprentice in his home, the student devotes his attention to mastering the stories.”

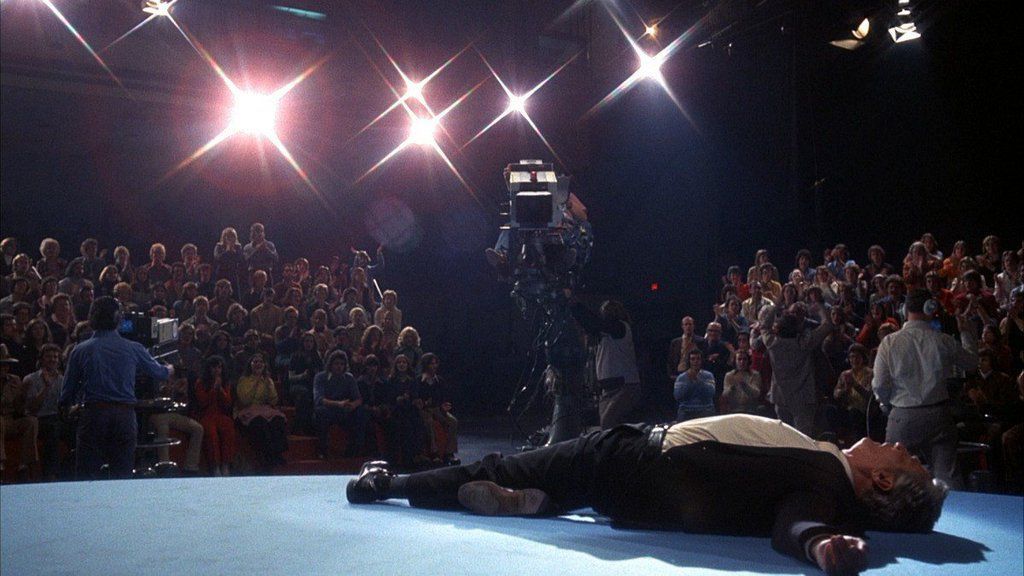

“The sense of reality is maintained throughout the story, and shared by performer and audience alike. Drawing freely on his personal experience, the performer styles his own individual pre- amble or “pillow” (makura t) for his story, selecting among con- temporary events, the weather, or work, whatever topics he feels his audience might be interested in. When he enters into the story itself, then his hero, in a curious and sudden shift of time dimen- sion, leaps out of the setting of an old tale right into the present moment and confronts the audience. Here, if the storyteller clumsily tries to evoke laughter in an obvious way, the effect will amount to nothing more than crowd-pleasing titillation, and his story may fall flat. But the expert performer can bridge the time gap smoothly and without a hitch, drawing the audience along with him into the world of classical rakugo.”

“The rakugo performer must organize his story in a new way each time, but if he is to remain within the confines of classical tradition, he is forced to observe certain definite rules. Throughout several centuries of rakugo the main plots of the stories and the heroes’ names have not changed. In the organization and minute descriptive details of episodes, with each performance, each year, and each generation, a great variety of different nuances and changes have appeared. No story can ever be performed twice in exactly the same way.”

“Changes in scene of a story are described by onomatopoetic words and sounds; for example, the ringing of a temple-bell, bon-bon; the clatter of wooden clogs, karan-koron; the sound of the wind, pyiu u u u; rolling of stones, gara-gara; or noise in the background, di-di, go-go. Onomatopoetic insertions can extend over a period of more than one minute, when they describe such movements as slow walking, tata tata…, tsun tsun …; running, sai-sai koro-sai, e-sa-sa, sowa- sowa, chowa-chowa; walking with heavy baggage on one’s shoulders, wasshoi-wasshoi…, or the sounds of work and play, kachi-kachi, pachi-pachi, pochi-pochi, poka-poka, potsu-potsu, sara-sara; or heavy exertion, hora-yo, sora-yo,yosshoi.”

“The rakugo performer is not supposed to change his position once he takes a seat on the stage. But merely by the movement of the upper half of his body he represents all kinds of actions. Walking from one place to another is expressed by one of the most amusing gesture formulas of rakugo: the performer withdraws his hands into the wide sleeves of his kimono, his knees, hips, and shoulders sway rhythmically, and he talks to himself in a murmuring voice, as if lost in thought. The audience knows that a person is on his way to an- other place; they also know that he will suddenly be startled out of his thoughts by an unexpected event, and they anxiously wait for that moment.”

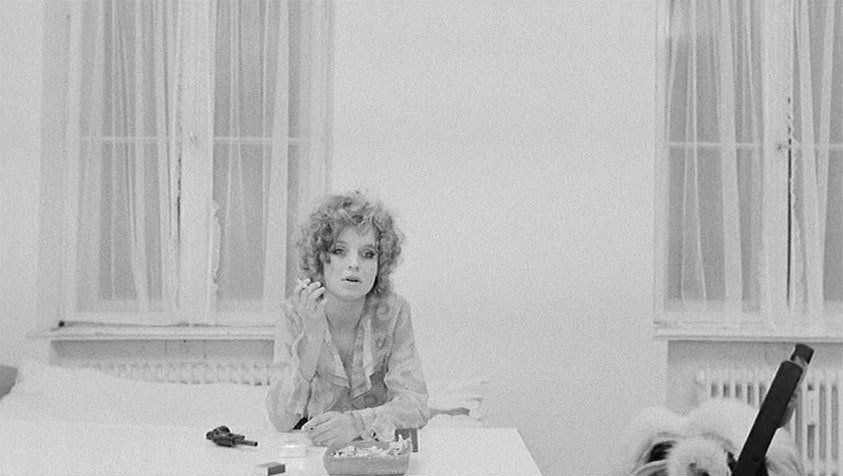

“The focal point of the rakugo story is the world of everyday. Many of its cast of characters strut about dressed in sundry garb and historical costumes, but they are part of the storyteller’s world and the world of his audience. From there the rakugo performer takes the models which he fits into various stereotypes according to class and profession: the feudal lord, the military man, the priest, the scholar, the retired head of the house, the working-class man, the farmer. At times the principal characters are complete outsiders that do not fit into ordinary societal roles: the cheapskate, the thief, the liar, or the prostitute. Sometimes it is just the simpleton, the lazy- bones, the miser, the boozer, and the conniver that pass across the imaginary rakugo stage. There are, of course, no detailed portrayals of people as individuals. This is the major difference between rakugo and pure literature. While there are instances where a character is provided with a definite personality, there are practically no examples of that personality changing as the story develops.”