Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Innovations

- Artistic intentions

- Theatrical style

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Influence

PC: So she has this big new space – the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, what attracts her to Adolphe Appia’s ideas about design? Was it her awareness of the designer or was it more organic than that?

NH: I think it is more to do with the designer that they worked with – John Bury, who went on to be the National Theatre’s key stage designer later on in the 60s. He was around for a long, long time in that early period. He was one of the linchpins of the company. He was also someone that was reading widely and extremely knowledgeable about other designers globally. He tried to bring their influences into the British theatre. Again it was about reacting against what the British theatre was – drawing room comedies or light dramas, or the very beautiful, highly produced productions of Shakespeare. Bury wanted to move away from that to provide a different set of theatrical images. In the beginning there were these very stark beautifully, side-lit productions. People didn’t side light things in the way that Theatre Workshop did.

Operation Olive Branch (Theatre Workshop’s version of Lysistrata)

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

They used these shafts of light, ramps, turrets; creating quite dark, stark atmospheres. Or a map that goes across the entire stage: it still would look modern now.

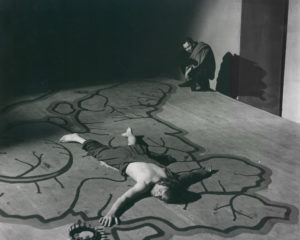

Edward II

Edward II

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

That then evolved with the work. You then get these hyper-realist pieces like You Wont Always Be On Top and A Taste Of Honey to a certain extent, The Quare Fellow, which is set in a prison, they had the yard and the bars. They also used the backdrop of the actual theatre space so that it didn’t have curtains coming across as was traditional. They would use the raw brick work of the back of the stage space: all of the piping and the industry of the stage space is part of the environment.

PC: Were her working practices with designers during a production distinctive from the contemporary theatre?

NH: I think it was Ivor Dykes who was the sound engineer of Oh What a Lovely War, he said something like, “You never had dress rehearsals, never had tech rehearsals. The technical side was always developed alongside the creative side.” I think that was probably quite a different approach to what was going on at the time. It wasn’t the director saying, ‘Yes we’ll have this and we’ll have that’ but it was the designers, John Bury, and other people later on, working alongside Littlewood, making it all work organically as the process evolved.

PC: That sounds similar to how Emma Rice and Kneehigh work despite restrictions of budgeting (https://kneehighcookbook.co.uk/interview-malcolm-rippeth/). I know Kneehigh take inspiration from Littlewood and they acknowledge her as a big influence. You can see it in her first Shakespeare production, responding to the community. And 946: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips seems a direct descendent of Oh What a Lovely War. I think that it is fantastic for such a prominent female director and company to make those connections.

NH: There is a very similar kind of rumbustious quality about their work, certainly in Littlewood’s later work, there are real links with Kneehigh.

PC: Also their local approach, they are responding to their community in Cornwall, the continuous loop. Kneehigh obviously have huge technical scope with their productions, what were the limitations of technology when Joan Littlewood was working? You mentioned side lighting was uncommon, was that because there hadn’t been the technological innovations?

NH: I’m not sure, because I presume side lighting would have been used in dance from my limited knowledge, rather than being used in theatre productions. It was a shift to something more atmospheric for Theatre Workshop; rather than just lighting what was happening, they were moving to using lighting as something which was about atmosphere, mood, tone: part of the texture of the performance. That was different. Lighting was usually used to show the actors off in a good light, not creating the mood, atmosphere and tension of Littlewood’s theatre.

PC: Was there anyone around Europe who would have influenced John Bury?

NH: In terms of the lighting they all cite Adolphe Appia as being the primary influence and Edward Gordon Craig’s use of architectural shapes was important too.

Summary

- John Bury, Theatre Workshop’s designer was reading widely and extremely knowledgeable about other designers globally. He tried to bring their influences into the British theatre.

- In the beginning there were these very stark beautifully, side-lit productions. People didn’t side light things in the way that Theatre Workshop did.

- They also used the backdrop of the actual theatre space so that it didn’t have curtains coming across as was traditional.

- The technical side was always developed alongside the creative side.

- There are real links with Kneehigh. There is a very similar kind of rumbustious quality about their work, certainly in Littlewood’s later work.