Tag: Theatre Workshop

Everyone should study A Taste of Honey and Oh What A Lovely War in Drama.

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Influence

- Key texts

PC: Thank you. I hope our discussion will help spread the word of Joan. I think the character you describe will appeal to teachers and students. And the fact that she is, kind of, Stanislavski, Piscator, Brecht and Grotowski all in one.

NH: What I think is really useful with Littlewood, that you don’t get with Stanislavski, is that you have the texts there. You can see those ideas in terms of training, in terms of the way that the stage space should be, and how characters should interact. You’ve got it there as a resource. Everyone should study A Taste of Honey and Oh What A Lovely War in Drama.

PC: Yes. It is a great strength of Littlewood’s work that her techniques have become so common place. Unfortunately, it is also a weakness, as people forget or overlook how revolutionary she was because her influence is everywhere.

Summary

- Teach people about Joan Littlewood and how her influence is everywhere

Littlewood and Theatre Workshop’s Oh What a Lovely War: A Collision Montage

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Use of theatrical conventions

- Theatrical style

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

PC: Let’s return to her most famous production: Oh What a Lovely War. How did they devise the play?

NH: Improvisation was used to generate the material. They worked with lots of research: materials would have been brought in. Lots of books were coming out about the First World War, a TV documentary had been on about it as well. So there was lots of documentary material that they were trying to work their way from, to find the best way of articulating it on the stage. Improvisation was used as a way to devise from that material. How do we devise from this material to make this work?

PC: Are there records of that process?

NH: There aren’t records of the process but there are people who worked on the show. There are various interviews with people who worked on the show. It wasn’t a formalised process at all, there was no document. She kept notebooks in the early period that I have seen but there is nothing from the later periods at all. She was just making it up as she went along. She kept herself in the moment of creating.

PC: So how did she control her approach to making the work?

NH: The research process was quite academically orientated although she didn’t necessarily like academics. She’d go and do lots of reading, bring source material in, she would give the company particular areas to research: maybe a particular battle or a particular period in the war or a particular figure like Hague or Marshall and people would then bring that material into the rehearsal room. They’d see something that was interesting and follow that.

PC: And how did they logistically make sure that they repeated things. Did they have a writer working alongside. How did it get set?

NH: No, it just got set by doing. There wasn’t a scribe taking down notes. It was an organic process that evolved until the scenes were relatively set.

PC: Did the spirit of improvisation spill over into performance?

NH: In performance it was used to try and keep things sharp and alive. One of the differences with the majority of the theatres of the day was that you rehearsed something, you blocked it, you set it, and then it was about repeating that night after night, after night. For Littlewood that was deadly theatre. She wanted to keep a frisson going in the actual performances: she would invite moments of improvisation just to shift things up a bit. Sometimes she wouldn’t even tell the rest of the actors on stage, she would give somebody an instruction to do something completely new, which would make the other performers have to respond to this new piece of action that was going on. An example of that from Oh What A Lovely War, is a rugby team that had taken a block booking and she organised for them to walk on stage when Barbara Windsor sang the We’ll Make A Man Of You song. So she gave Barbara something to deal with in the moment of performance just to constantly keep things fresh and alive and in the moment of performance. Rather than just regurgitating what had happened the night before and the night before that. So improvisation was important for those things.

PC: How did the popular tradition of variety and the Music Hall influence Littlewood’s work, specifically in Oh What a Lovely War?

NH: The Music Hall was seen as an authentic working class, popular cultural form by Littlewood, that is why she warmed to it. There was a relationship between the stage and the audience, a back and forth, that goes on in those forms. As well as literally being about variety. What happens when you have lots of things happening on the stage at the same time? Or that idea of the collision montage in terms of Oh What A Lovely War. There is something in the format of Music Hall and variety, a series of turns, that is quite theatrically effective. Whereas in Music Hall and variety they were individual turns she kind of flips that idea around. What if the theatre event is effectively a series of turns but they are all thematically interconnected, like in Oh What A Lovely War?

And the Pierrot show, which she obviously used in Oh What A Lovely War, that again is part of that popular seaside tradition. The Pierrots were around during the period of the First World War. They get referred to as the Merry Roosters and there actually was a troop called the Merry Roosters during the First World War. So she is taking that popular form and reference very clearly into the play.

Summary

- Lots of research was done during the creation of Oh What a Lovely War and improvisation was used to generate the material.

- Littlewood was making it up as she went along. She kept herself in the moment of creating. There aren’t records of the process beyond anecdote.

- Littlewood wanted to keep the thrill of performance going so she would invite moments of improvisation just to shift things up a bit.

- There was a relationship between the stage and the audience, a back and forth, that goes on in Music Hall and Variety that appealed to Littlewood.

- Littlewood’s later work shows her interest in a theatre event that is series of turns that were all thematically interconnected, like in Oh What A Lovely War – the collision montage.

Littlewood: Music, Stanislavski and Laban in Performance

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Influence

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Innovations

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Theatrical style

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

PC: Stanislavski put a lot of emphasis on the idea of tempo/rhythm and again I see that in Littlewood’s work with Eurhythmics. Originally it was a theory for music, was music used in Theatre Workshop rehearsals? And how was it important in productions?

NH: Music became increasingly a part of productions, and songs certainly, when she started collaborating with Lionel Bart in Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be. She used a jazz band, famously on A Taste Of Honey stage. I’m not sure about rehearsals, I’m not aware that they did, but I think that they must have done in terms of the movement work that Jean Newlove did. Newlove trained and worked with Laban and then she joined Theatre Workshop and became their principal movement teacher.

PC: Was she scouted because of her interest in Laban?

NH: She wasn’t scouted she turned up, from memory, to one of the workshops they did when they were in Ormesby Hall and she ended up getting together with Ewan MacColl and marrying him. So it was a personal, as well as a professional thing. But she got taken on for her connections with Laban and being able to do the movement training that Littlewood and MacColl were cobbling together themselves up to that point. Now they then had someone who was an expert to do it properly.

PC: Was she influenced by Brecht’s work?

NH: Not so much consciously. They did do a production of Mother Courage. They got the rights to do the British premiere of it, which was a disaster. He only gave the rights if she would perform Mother Courage because she did perform in the early days. She didn’t want to do it and she did a poor job. It was done in Barnstaple in Devon and that was it. So no not consciously, I think she found it quite cold, which I don’t necessarily agree with but she found it as an overly intellectual theatre.

PC: Interesting that that unfortunate perception of Brecht still stands for so many. Can we talk about specific actors? Who was her leading female actress?

NH: Avis Bunnage often took the main roles.

PC: And leading male actors?

NH: Harry H. Corbett, the son from the TV programme Steptoe and Son. He was married to Avis, in the early years they came as a package. Richard Harris started off doing Theatre Workshop stuff as well. Howard Goorney who wrote The Theatre Workshop Story was always in those early pieces and trained as part of the company, I think he was part of the 1930s group and stayed all the way along. Murray Melvin, was Geoff in A Taste Of Honey and he was in Oh What A Lovely War. He is still the archivist at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East now.

PC: How important is improvisation as part of process in Littlewood’s work?

NH: Improvisation was used as a way of trying to make things real in performance. For A Taste of Honey she had Avis Bunnage and Frances Cuka walking around the theatre for hours carrying really heavy suitcases, getting them to improvise arguing with landlords and landladies, getting wet, waiting for buses, you know, arriving places, getting closed doors, moving on. Then they started working on the opening scene when they arrive in the bedsit. So they used improvisation as a way of getting to a truth, a realness on stage. So that was in the preparation for performance.

PC: These long preparatory improvisations to reach a truth, a realness, have parallels with Grotowski and his via negativa approach.

NH: Clive Barker, who was part of Theatre Workshop and wrote the book Theatre Games, talks about her using via negativa as well. Try this, try this. Never try it LIKE this. Try it again, try it again until you find the right moment. He linked that to Grotowski. That doesn’t necessarily suggest that it was a direct influence but it was a similar use of the technique.

PC: Did she feel that she had to strip over-trained actors back for them to be able to perform in her work?

NH: She just wouldn’t take them.

PC: So she knew the type of person that would be able to do it. What were the actors reactions to the continuous training?

NH: They completely bought into it initially. The initial company were an ensemble, they wanted to train and they wanted to work in this different way: they were a merry band of brothers: joining together with a common purpose. I think later on at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East it became quite a shock for actors coming in because she wouldn’t want to do a traditional audition process. Murray Melvin tells a lovely story of coming into audition for her and she said “Do you have your speeches prepared? Yeah. Do you want to do them? No. Let’s not bother then just tell me a story.” For her it was about courage. Another actor tells a story about her throwing a script at them and saying, “Right I want you to read all the parts. What? But I want to read the part… No I want you to read all of them: men women, children old men, young women” And he did and felt ridiculous and probably looked ridiculous but her response was “well if you can do that and you’re prepared to make a fool of yourself then you’d probably be a very good actor.” Another well known story is of Barbara Windsor meeting the cleaner scrubbing the steps of the Theatre Royal: they were chatting, then it turned out the cleaner was Joan Littlewood and she got the job at that moment. There are loads of great stories! Victor Spinetti who was the MC in OH What A Lovely War, she picked him, after he was compering in a strip joint. So she picked people up in strange places. She’s not going to go and pick up someone who’s RADA trained. She was more likely to go and get people from the variety or the clubs. She wanted actors with that curiosity and a willingness to play and take risks. If you weren’t prepared to do some training then what was the point? The spirit of experimentation was important.

Summary

- Music was an important part of performance and rehearsals.

- They got the rights to do the British premiere of Brecht’s Mother Courage but it was a disaster. She found Brecht rather cold and overly intellectual.

- Improvisation was used as a way of trying to make things real in performance.

- The initial company were an ensemble, they wanted to train and they wanted to work in this different way.

- Littlewood made sure she got the actors she wanted by searching strange places and conducting unconventional auditions.

Littlewood’s Actor Training – The Composite Mind

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

email: n.holdsworth@warwick.ac.uk

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Theatrical purpose

- Innovations

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Influence

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

PC: What was Littlewood’s approach to training actors?

NH: In the commercial theatre at the time you went off as an actor and did your actors’ training; then you would finish your actors’ training; then you would act; then you get your script, you would learn your part then you would perform your roles. In contrast, Littlewood believed that you always kept training and that was a big thing that distinguished her from other directors at the time and still! So always, in those very early years up to the mid-1950s, they were still doing daily movement training; vocal training; improvising; doing Stanislavski exercises. She’s doing things that would always keep the actors on their toes. Laban was hugely influential on Littlewood. That sense of wanting the actors to constantly be thinking about how they move their bodies in space. What that means in terms of weight, flow, speed, rhythm. Equally vocally: having a dexterous voice and being able to manipulate that. Not just coming on stage doing your lines and off you go. Instead her actors were really grounded, fully thinking, creative people. Not only training them as individual actors but also instilling a belief in collaboration. She had this phrase ‘the composite mind’ – I think it is an important one. The importance of collaboration: that theatre is something that is done together. You needed to learn that; you needed to learn that as an ensemble. The ensemble wasn’t something in the British theatre tradition at the time, you had a company and you hired your actors for that particular production. Companies didn’t work in that ensemble way, in the way that Littlewood wanted them to do: training the actors.

PC: Is there a pinpoint moment when she discovered Stanislavski in particular and Laban?

NH: Really early!

PC: Before Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood’s first English translation of 1937?

NH: I don’t think that it was pre-that translation but she was certainly using it in the 1940s. I have seen some of her early notebooks and she is absolutely ripping off An Actor Prepares! Doing workshop notes of things that she is going to do and giving lectures on Stanislavski to people who turn up to do her sessions. So she would run this quite ad-hoc training thing.

PC: I think the dates of those Hapgood translations offer real insight into how advanced Littlewood’s training methods were. Benedetti’s introduction to the most recent translations explains how the staggered translation of Stanislavski’s writing led to massive misunderstanding of his theories on training.

Hapgood’s Stanislavski translation – dates of publication:

An Actor Prepares – 1937

Building a Character – 1950

Creating a Role – 1961

The first book covers the first year of Stanislavski’s proposed course and talks about the more psychological and cerebral methods, whereas the second and third bring have an emphasis on physical action. The circumstance of publication, the growth of the American Method, as well as a simple neglect of those last two texts led many to overplay the idea of Stanislavski as cerebral and psychological in approach rather than rooted in the physical. So for Littlewood to combine the psychological strategies of An Actor Prepares with Laban and Meyerhold’s physical approaches was truly innovative. This combination has now become common place with actor training and the development of ‘physical theatre’.

NH: Yes this three-pronged approach of Stanislavski, Laban and Meyerhold is innovative and influential. You wouldn’t think that they had a relationship with each other but they absolutely do in Littlewood’s practice.

Summary

- Littlewood believed that you always kept training and that was a big thing that distinguished her from other directors at the time and still!

- Stanislavski’s An Actor Prepares influenced Littlewood’s approach to training and rehearsal.

- Laban was hugely influential on Littlewood. That sense of wanting the actors to constantly be thinking about how they move their bodies in space.

- Meyerhold’s Biomechanics also influenced her work on physicality and movement.

- Littlewood’s combination of the psychological strategies in An Actor Prepares with Laban and Meyerhold’s physical approaches was truly innovative.

Littlewood and Design

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Innovations

- Artistic intentions

- Theatrical style

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Influence

PC: So she has this big new space – the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, what attracts her to Adolphe Appia’s ideas about design? Was it her awareness of the designer or was it more organic than that?

NH: I think it is more to do with the designer that they worked with – John Bury, who went on to be the National Theatre’s key stage designer later on in the 60s. He was around for a long, long time in that early period. He was one of the linchpins of the company. He was also someone that was reading widely and extremely knowledgeable about other designers globally. He tried to bring their influences into the British theatre. Again it was about reacting against what the British theatre was – drawing room comedies or light dramas, or the very beautiful, highly produced productions of Shakespeare. Bury wanted to move away from that to provide a different set of theatrical images. In the beginning there were these very stark beautifully, side-lit productions. People didn’t side light things in the way that Theatre Workshop did.

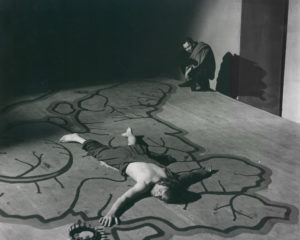

Operation Olive Branch (Theatre Workshop’s version of Lysistrata)

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

They used these shafts of light, ramps, turrets; creating quite dark, stark atmospheres. Or a map that goes across the entire stage: it still would look modern now.

Edward II

Edward II

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

That then evolved with the work. You then get these hyper-realist pieces like You Wont Always Be On Top and A Taste Of Honey to a certain extent, The Quare Fellow, which is set in a prison, they had the yard and the bars. They also used the backdrop of the actual theatre space so that it didn’t have curtains coming across as was traditional. They would use the raw brick work of the back of the stage space: all of the piping and the industry of the stage space is part of the environment.

PC: Were her working practices with designers during a production distinctive from the contemporary theatre?

NH: I think it was Ivor Dykes who was the sound engineer of Oh What a Lovely War, he said something like, “You never had dress rehearsals, never had tech rehearsals. The technical side was always developed alongside the creative side.” I think that was probably quite a different approach to what was going on at the time. It wasn’t the director saying, ‘Yes we’ll have this and we’ll have that’ but it was the designers, John Bury, and other people later on, working alongside Littlewood, making it all work organically as the process evolved.

PC: That sounds similar to how Emma Rice and Kneehigh work despite restrictions of budgeting (https://kneehighcookbook.co.uk/interview-malcolm-rippeth/). I know Kneehigh take inspiration from Littlewood and they acknowledge her as a big influence. You can see it in her first Shakespeare production, responding to the community. And 946: The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips seems a direct descendent of Oh What a Lovely War. I think that it is fantastic for such a prominent female director and company to make those connections.

NH: There is a very similar kind of rumbustious quality about their work, certainly in Littlewood’s later work, there are real links with Kneehigh.

PC: Also their local approach, they are responding to their community in Cornwall, the continuous loop. Kneehigh obviously have huge technical scope with their productions, what were the limitations of technology when Joan Littlewood was working? You mentioned side lighting was uncommon, was that because there hadn’t been the technological innovations?

NH: I’m not sure, because I presume side lighting would have been used in dance from my limited knowledge, rather than being used in theatre productions. It was a shift to something more atmospheric for Theatre Workshop; rather than just lighting what was happening, they were moving to using lighting as something which was about atmosphere, mood, tone: part of the texture of the performance. That was different. Lighting was usually used to show the actors off in a good light, not creating the mood, atmosphere and tension of Littlewood’s theatre.

PC: Was there anyone around Europe who would have influenced John Bury?

NH: In terms of the lighting they all cite Adolphe Appia as being the primary influence and Edward Gordon Craig’s use of architectural shapes was important too.

Summary

- John Bury, Theatre Workshop’s designer was reading widely and extremely knowledgeable about other designers globally. He tried to bring their influences into the British theatre.

- In the beginning there were these very stark beautifully, side-lit productions. People didn’t side light things in the way that Theatre Workshop did.

- They also used the backdrop of the actual theatre space so that it didn’t have curtains coming across as was traditional.

- The technical side was always developed alongside the creative side.

- There are real links with Kneehigh. There is a very similar kind of rumbustious quality about their work, certainly in Littlewood’s later work.

Littlewood, Theatre Workshop and the Move to Theatre Royal, Stratford East

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth: Part 5

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

email: n.holdsworth@warwick.ac.uk

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Theatrical purpose

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Theatrical style

- Influence

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

PC: I know that she enjoyed touring, did this inform her relationship with space? Did they always have ambitions to be in one space?

NH: They were touring when Theatre Workshop formed in 1945 and they toured until the end of 1952. The ambition was always to try and reach this working class audience that would completely get what they were doing but it never really happened. It happened sometimes, but mostly not. They’re touring little theatres around the Lake District and then going up to Scotland, mainly travelling around the north. The decision to move to the Theatre Royal, Stratford East was really because they were poverty stricken. They were doing one night stands left, right and centre and not able to make a living; they were living this really hand to mouth existence. The opportunity at the Theatre Royal, Stratford came up and I’m not sure what the exact arrangements were but the theatre manager, Gerry Raffles, who was her partner by that stage led the move. But the company was reluctant as they saw it as a sell out, particularly Ewan MacColl and he didn’t go with them to Stratford East. He refused and as one of the founders of the company that was a big deal. His view was that the move to London would mean that they would then be courting the critics; they’d be really small fish in a big pond, having to play the game of the commercial theatre world. He believed they wouldn’t be reaching the broad working class audience that he was really keen to try and attract. The counter argument that Littlewood presented was that Stratford East is a working class community, so rather than going out and trying to reach those communities, those people, those audiences, let’s try and work within a community. She wanted to get that local working class community into that space – the continuous loop. They did a lot of work to try and achieve that: they made lots of connections with trade union organisations: getting write ups in the local newspapers; commissioned a local journalist, Anthony Nicholson to write about the local railway industry which was a big employer in the area, a play called Van Call. So, in terms of the space, that was the journey if you like.

PC: Did they venture out much during that time in Stratford East, back to the job centre queues?

NH: No not until that shift back to the work at the end in the late 1960s and early 70s and even then it was more about animating communities through fairs and fun palaces rather than political activism in the traditional sense.

PC: So how did they get people into this new theatre out in East London?

NH: There was a distinct body of work that was done around the classics including her productions of Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Johnson. Again that was about responding to what was going on at the time in terms of the productions of Shakespeare; it was the time of Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud. All very much about these heroic leading figures, about the beauty of the verse being very predominant. She wanted to bring the social guts back to Shakespeare and did these amazing productions: Richard II, Edward II, she did Arden of Faversham: a little known Renaissance play. Influenced by Adophe Appia, they were very stark visually: stark, plains of light and ramps. It was about bringing the social world of Shakespeare into play; it was about political intrigue; it was about power and who has power, who doesn’t have power; how do people lose their humanity in the search for power. It was about coming out of the Second World War and responding to those big political ideas. Doing Macbeth, for Littlewood, becomes even more pertinent at the time. But she sees all these very glossy, glamorous productions of Shakespeare and thinks: “No that’s not it! Absolutely no! That is not what this is!” She was interested in the guts the gore and personal, political ambitions. She wanted to get that social world in with the Shakespearean productions that she did. Then there was another shift: she had got a good reputation for putting on these really imaginative and creative and vibrant theatrical pieces. So writers started sending her unsolicited scripts, she got sent 19 year old Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey and she got sent Brendan Behan’s The Hostage and The Quare Fellow and then local writers as well – You Won’t Always Be On Top was by Henry Chapman an actor who had started to do a bit with Theatre Workshop. It evolves, if you like, rather than there being a conscious decision to say I’m now going to do my Shakespeare. It just evolves.

Summary

- The decision to move to the Theatre Royal, Stratford East was really because they were poverty stricken.

- The company was reluctant as they saw moving to London as a sell out, particularly Ewan MacColl and he didn’t go with them to Stratford East.

- Stratford East was a working class community, so rather than going out and trying to reach those communities, those people, those audiences, Littlewood wanted to try and work within a community.

- She wanted to bring the social guts back to Shakespeare and did these amazing productions influenced by Adophe Appia, they were very stark visually.

- Writers started sending Littlewood unsolicited scripts: she got sent 19 year old Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey and she got sent Brendan Behan’s The Hostage.

Littlewood’s Approaches to Texts and Devising

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth: Part 4

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

email: n.holdsworth@warwick.ac.uk

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Key collaborations with other artists

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

- Influence

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

PC: Is there a clear difference in her work with text compared to her devised pieces?

NH: Yes. The form was always about making it work with the text, so whatever the text required was the form that was made. Or in terms of the more improvised pieces like Oh What a Lovely War or earlier plays like John Bullion it was about the best relationship between the different elements of production. Derek Paget uses a term collision montage which I think is a really lovely way of talking about that work. She constantly reordered scenes making something like Oh What A Lovely War, to see what was going to have the most impact: put that next to that, what does that do? Try it again here, what does that do?

PC: I know that Littlewood was very playful with her actors: was her experimentation with form rooted solely in her playfulness or was it rooted in a research and understanding of the theatre?

NH: I think it changes given the different contexts she was working in.

- In the beginning the impetus was political

- then it moved through to wanting to make really vivid theatrical imagery

- then the idea of the authentic working class voice becomes more important (A Taste of Honey, You Won’t Always Be On Top and Brendan Behan’s plays)

- Then she shifts into wanting to be much more improvisational, breaking down that relationship between the auditorium and the stage space with interruptions and humour to develop a relationship with the audience.

- Then after Oh What a Lovely War she gets completely bored with theatre and theatre spaces full stop and she starts doing community projects for kids and makes plans for this big cultural centre – the Fun Palace. This idea lives on in the Fun Palace events run across the world at the start of October led by co-directors Stella Duffy and Sarah-Jane Rawlings.

So yes there is definitely the sense of her anarchic spirit driving these shifts but it is also about her ever growing knowledge of the theatre that never allowed her work to stay still.

Summary

- Littlewood constantly reordered scenes making something like Oh What A Lovely War, to see what was going to have the most impact. Derek Paget uses a term collision montage.

- Littlewood’s anarchic spirit drove shifts in her approach but changes always came about with her ever growing knowledge of the theatre.

Littlewood’s Continuous Loop and the Authentic Voice

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth: Part 3

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

email: n.holdsworth@warwick.ac.uk

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Influence

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- Theatrical style

- Innovations

- The relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

PC: What was her existence during the Second World War? Did she continue making theatre?

NH: She was making a living by doing lots of radio. There is an early period when she went to Manchester because she’d met a guy called Archie Harding at RADA. He’d come and examined a verse speaking competition that she’d won. So she went off to search for this guy and he offered her work at the BBC. This led to her doing quite a few documentary pieces; most famously a piece called The Classic Soil. She’d go out, again you can see real links with the theatre, she’d go out and interview ordinary people in their ordinary working or living environments and just talk to them. She had a big thing about wanting to hear the authentic working class voice.

PC: How common was the documentary style that presented the authentic working class voice?

NH: Not common at all; it was a really new thing; it was again with Ewan MacColl. We mustn’t underestimate the importance of him in that early period. The two of them were totally in cahoots and developing things. It is worth looking up The Classic Soil.

PC: This search for an authentic voice and specifically an authentic working class voice in Joan Littlewood’s work, along with Erwin Piscator’s Living Newspaper technique and Peter Cheeseman’s Stoke documentaries, are seen as early examples of what has become known as verbatim theatre. Joan’s legacy can be seen in Alecky Blythe’s Little Revolution or Dan Murphy’s new play Carry on Jaywick. Are there examples in her theatre work that were influenced by the radio documentary form?

NH: Yeah, I think definitely that idea of presenting the authentic voice is a root of modern verbatim theatre. She felt the authentic working class voice wasn’t being heard on the British stages at that time so it became really important to her. A good example is a play called You Won’t Always Be On Top (Henry Chapman), which was set on a building site. It was one of the plays that she did in the 1950s in which she collaborated very closely with the writer and the script was evolving in rehearsals, which happened a lot with her work. She took all the performers off to a building site and they had to learn how to build a wall because they had to build one in the production every night. She had this incredible replica of a building site on stage. But more important than the visual authenticity, was the focus on patterns in the voice. Joan wanted to have that very real quality of back and forth banter that happens in lots of contexts, but this building site in particular. I think that idea of trying to document and record and authenticate the voice does have a line through to verbatim theatre today.

PC: In terms of records of those things. Is there the play text?

NH: Yes there is the play text of You Won’t Always Be On Top and there are some great photographic images as well. Another is The Long Shift, a play she wrote with Gerry Raffles, who became her partner.

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

It is about miners down a mine shaft so you see that attempt at visual authenticity there.

This is the set for You Won’t Always Be On Top.

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

Courtesy of Theatre Royal Stratford East Archive Collection.

You can see she is trying to create a truthful recreation, a very naturalistic looking environment.

PC: She is not usually associated with that style of work.

NH: No but it was a major part of what she did. I think that is one of the things that is really interesting about her: there is no set style. She believed that theatre should always be organic, made in the moment.

PC: The authentic voice seems to be an important debate at the moment, in the theatre and broader society. Theatre is accused of being too London centric, whilst the country, post-EU Referendum, as a whole is suffering a disconnect with working class people, particularly illuminated by the Labour Party’s current identity crisis. So a hypothetical question: How might Joan Littlewood respond to modern Britain in terms of creating her theatre?

NH: She referred to the idea of the continuous loop between the theatre, the audience and the local community. So I think it would be interesting to think about what the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, has become. When Littlewood was there it was a staunchly working class environment predominantly. It is now an incredibly multi-ethnic community and the theatre has evolved to reflect that community. Theatre today, like in Littlewood’s day, is predominantly a white middle class pursuit but at Theatre Royal, Stratford East it absolutely isn’t. It is one of the most diverse audiences and I think that is because they work with that ethos of the continuous loop. You have to go out into the community, find out about the people, who the people are, what their narratives are, what the voices are, what the stories are that they want telling. Then you go back into your theatres and you make that work, you commission it, you make it.

Summary

- Ewan MacColl was an important part of Joan Littlewood’s life and career in that early period. We mustn’t underestimate the importance of him.

- Littlewood had a big thing about wanting to hear the authentic working class voice. She’d go out and interview ordinary people in their ordinary working or living environments and just talk to them.

- The idea of trying to document and record and authenticate the voice does have a line through to verbatim theatre today.

- You Won’t Always Be On Top and The Long Shift had a set that tried to be a truthful recreation, a very naturalistic looking environment.

- The continuous loop: you have to go out into the community, find out about the people. Then you go back into your theatres and you make work in response to what you find.

Littlewood’s Context and her Political Convictions

Interview with Nadine Holdsworth: Part 2

Nadine Holdsworth is Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. Her research has two distinct, but sometimes interconnected strands in Twentieth Century popular theatre practitioners and theatre and national identities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. She has worked particularly on Joan Littlewood and has written Joan Littlewood for the Routledge Performance Practitioners Series in 2006 and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre with Cambridge University Press in 2011.

email: n.holdsworth@warwick.ac.uk

Connections to the GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- Social, cultural, political and historical context

- Theatrical purpose

- Innovations

- Key collaborations with other artists

- Influence

- Theatrical style

- Significant moments in the development of theory and practice

- Methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

PC: What was most important to Littlewood at the start of her career?

NH: I think it was the political convictions. The fact that she became involved very early on in the 30s with Ewan MacColl and the Workers’ Theatre Movement. She had gone to RADA, left RADA because she couldn’t bare the sterile nature of the theatre that she was expected to do: the “anyone for tennis”, “cup and saucer” theatre which she abhorred. So she’s looking around saying look we’ve got some people here doing hunger marches, we’ve got a general strike, there are people that are in an extreme state of poverty and the theatre of the day is simply not addressing those social, economic, political issues. So that was the galvanising force initially: a real political impetus married with this passion for theatre and how theatre could be a voice for that experience. Theatre offered a way of approaching it, tackling it, investigating it in a way that would also be entertaining. Theatrically, at the same time, she is a real magpie, getting interested in the European theatre traditions. She is one of the early people in Britain, with Ewan MacColl, to start looking at Stanislavski, Piscator and Meyerhold and thinking – “These are great!” – whereas the British theatre tradition was still very much a text heavy theatre – the voice of the ac-TOR speaking. She thought no, there are these people that are doing these incredible theatrical pieces of work that she was really excited about. So I think that initial period was about trying to marry a theatre with a political impetus and an entertaining theatricality. But also about experimenting and how she could be a magpie and pick on all these influences she was seeing from abroad.

PC: What was her first stylistic response to that political impetus?

NH: Mainly that the theatre of her day was not how it should be. She was very much reacting against what she was seeing in the British theatre. As well as the influence of what she was seeing from European practitioners and seeing a theatrical vitality that was exciting for her. I think the first works from the 1930s were quite expressionistic, with short scenes, many of them very visual. You’ve also got this Agitprop movement, the Workers’ Theatre style of theatre, which is out on the streets, pulling on a cart and doing work to people in unemployment queues, queuing up for labour exchange and for jobs. These companies would pull up and do these short sharp topical sketches. They used a visual short hand: the bowler hat or the top hat for the posh blokes and the flat caps for the workers. They were doing scenes that were trying to show the workers’ experience back to them.

PC: She was involved in a few companies. Did she have a company then?

NH: Yeah, the Theatre Union and that worked until the beginning of the Second World War when people went off to fight and then they reformed after the war as Theatre Workshop in 1945.

Summary

- People were doing hunger marches, there was a general strike, there are people that are in an extreme state of poverty and the theatre of the day was simply not addressing those social, economic, political issues.

- Theatre offered a way of approaching it, tackling it, investigating it in a way that would also be entertaining.

- She is one of the early people in Britain, with Ewan MacColl, to start looking at Stanislavski, Piscator and Meyerhold

- Stylistically she was very much reacting against what she was seeing in the British theatre.