Interview with Paul Allain

Paul Allain is Professor of Theatre and Performance and Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Kent, Canterbury. Since collaborating with the Gardzienice Theatre Association from 1989 to 1993 he has gone on to write extensively about the theatre. He has published several edited collections on Grotowski as part of the British Grotowski project.

Paul’s films about physical acting for Methuen Drama Bloomsbury will be published at Drama Online in Spring 2018 as Physical Actor Training – an online A-Z. Draft films are currently available at the Digital Performer website.

email: P.A.Allain@kent.ac.uk

Connections to the IB, GCSE, AS and A level specifications

- key collaborations with other artists

- methods of creating, developing, rehearsing and performing

- relationship between actor and audience in theory and practice

- significant moments in the development of theory and practice

PC: Were there any major events that took place during this period?

PA: They did the Theatre of Nations project in 1975 and invited Eugenio Barba, Peter Brook, Luca Ronconi, and André Gregory. They all came and there were workshops and talks. Five thousand people participated in the various projects. It was a very broad frame of activities that Grotowski oversaw as an ‘über-director’, if you like. Not really leading practical sessions himself, though some of them he would, but really letting the others develop their work.

PC: That sounds huge. Where did these explorations take place?

PA: They restored the barns in Brzezinka outside Wrocław as a natural location, away from the city, to do this work. They did projects like the Mountain Project that was outdoors. They would spend two days in nature and people would immerse themselves in water and in grain in non-urban spaces. Very experiential, we’d possibly call it therapy today, but it was never couched in that way. It seems very much of its time, in terms of the hippy culture, but in fact in Poland this only became more established later; so it was quite innovative for Poland then.

PC: Did these projects tour like the productions?

PA: Yes, some of the projects went to Australia, to France; they weren’t all located in Poland. At the same time as the active culture activities were going on, Apocalypsis cum Figuris was being shown as a performance. Grotowski used it as a way to meet people and bring them into the paratheatre work.

PC: Was that anyone of any ability?

PA: Yes. He advertised on the radio, he sent callouts via socialist youth networks. So in some ways, it was everyone, but it was also people who had a need for it: a desire. Again, some people have called it elitist, but it wasn’t elitism based on wealth or money or privilege, it was really an elitism of whoever wanted strongly enough to be there and to participate.

PC: Was there any selection process?

PA: Yes, because if you’re going to spend two days with someone, living together, running through the woods, doing these experiments, you need to iron out people who might be difficult: people who were there for egotistical reasons. I can understand the need for a selection process. It was inclusive but not totally inclusive; it was guided. They were trying to find people who had a real desire to change.

PC: It sounds quite religious, is there a connection with religion? You mentioned he was thought of as a guru.

PA: He was avoiding that, but I think that people invest what they want. The activities had a parareligious aspect to them I suppose. Anything where people are brought together, where they sing together, can become religious; but for him it was never about a god or divinities. That’s one of the things that Grotowski would have weeded out; people who were investing too much in him as a figure who would save them. He was very careful not to create an alternative religion at a time when cults and that kind of behaviour were being widely adopted or created. They did draw on religious iconography, like grains of wheat for example, but it was more in a very functional, practical way. There was some religious symbolism but equally he was inspired by a very broad range of cultural references such as from Sufism, Indian culture and Catholicism.

PC: How did the paratheatre phase of work come to an end?

PA: In 1976 they were in Venice, at the Biennale and Włodzimierz Staniewski, who went on to set up Gardzienice, had a bust up with Grotowski and left. He thought that the work had lost its point: it had become nebulous, too self-indulgent and lacked direction. He exposed the flaws that Grotowski later looked back on and thought were legitimate issues with the work. The next phase of work overlapped with paratheatre – Theatre of Sources. This went to a much more technical level, finding people around the world who had technical expertise and looked at the sources of theatre from different cultures in terms of ritual and musical practices and dance. All this was an attempt to understand where theatre begins.

Full interview here:

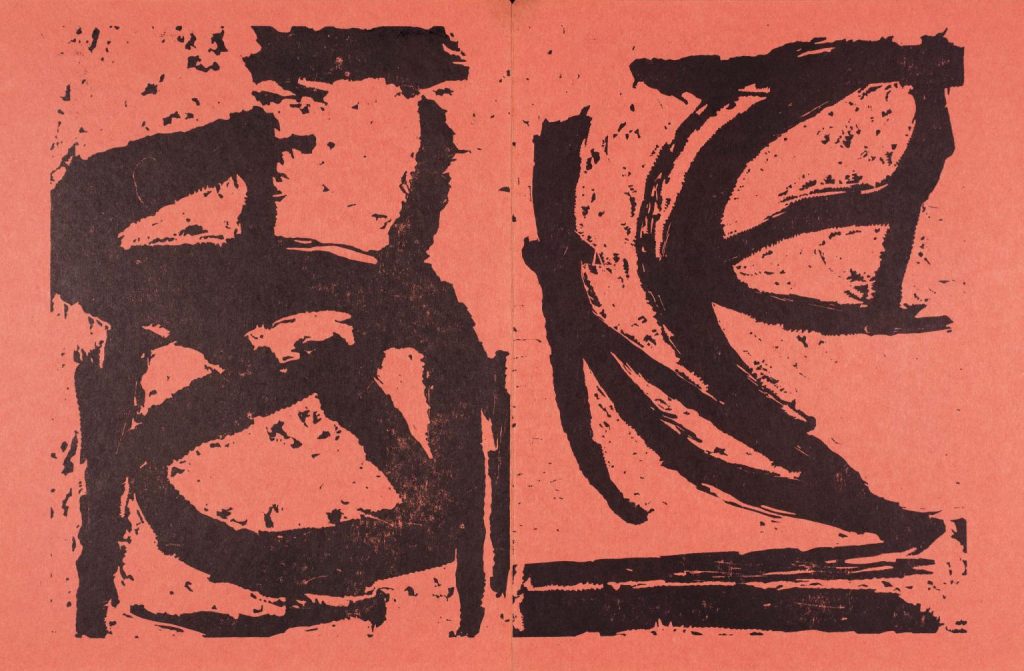

Grotowski